St Mac Duagh’s Hermitage is located in the townland of Keelhilla(Kinallia’Kinahulla) in the Burren Co Clare. According to tradition, the site was chosen by St Colmán Mac Duagh as a hermitage because of its isolation and solitude. The saint lived here as a hermit for seven years before leaving and setting up his great monastic foundation at Kilmacduagh.

‘What a dismal and gloomy spot!’ wrote Eugene Curry when speaking of St Mac Duagh’s Hermitage. These remarks were recorded in the Ordnance Survey Letters of Co Clare in 1839. In my experenece this description could not be more further from the truth. I consider St Mac Duagh’s hermitage to be a very scenic, peaceful and beautiful place.

Curry visited St Mac Duagh’s Hermitage on the 23rd October 1839 when carrying out his survey of the antiquities of Co Clare. He set off from Corofin and headed across the a karst limestone landscape of the Burren. The ground he travelled over was ‘uneven surface of limestone rock‘. The experience left Curry ‘fatigued‘ mentally and physically by the time he arrived at the ‘dismal valley‘. The hermitage is located at the base of Slieve Carrana cliff face in the townland of Keelhilla. It is very clear from his writing that his spirits were low by the time he arrived

What a dismal and gloomy spot! I walked thither on the 15th October from Corofin and I never felt so fatigued after having walked for miles across that country on the uneven surface of the limestone rocks. What an enthusiastic recluse St Colman, the son of Duach must have been to have retired from the busy scenes of life to contemplate eternity and uncertainty of human fate in the dismal valley then thickly wooded and haunted by wolves!

View of the Burren Co Clare from the path leading to St MacDuagh’ s Hermitage

The site has little changed from the time of the Ordnance Survey with the exception of the growth of scrub and trees surrounding the site.

The archaeological features at the hermitage are surrounded by a low wall composed of large moss-covered boulders.

View of enclousure surrounding church at St Mac Duagh’s Hermitage

The most imposing remains at the site are the remains of a small church or chapel, The Ordnance Survey Letters described the structure as

The little oratory of Mich Duach in this wild valley through much dilapidated is still easily recognised to be a church of his time. It was very small, and only one gable and one side wall remain.

Today the church is in poor condition only the east gable stands intact, the other walls remain in a varying state of preservation. Ní Ghabhláin (1995, 73) dates the church to late medieval period and there is no sign of later alterations.

Above the church is a small cave found in the cliff face. The cave was ‘called Mac Duach’s Bed or Leaba Mhic Duach‘ as the St Comán was ‘accustomed to sleep every night‘ (Ordnance Survey Letters).

I’m not sure you could call St Colmán a true hermit as during his retreat from the world he was accompanied by his servant. There is a lovely story about St Colmán’s servant.

One day his servant complained that he was hungry and St Mac Duagh replied that God would provide. There was a banquet at the time King Guaire’s castle in Kinvarra and at that moment the dishes of food suddenly rose and floated out the window. The surprised king and his men followed the dishes and were led to St Mac Duagh and his servant. But when the king’s party arrived at the hermitage their feet became rooted to the stone and they couldn’t move. Luckily for the king and his men, St Mac Duagh was able to perform a miracle and free them, whereupon the king was so impressed with St Mac Duagh he asked him to found the monastery of Kilmacduagh on the lowlands near Gort. While this was taking place St Mac Duagh’s servant was eating King Guaire’s food with gusto but unfortunately had grown so accustomed to the meagre diet he received in the service of St Mac Duagh that the banquet food killed him. Theses traditions are preserved to this day in the name of the track that leads to the hermitage, Bóthar na méisel, or ‘way of the dishes’, and the nearby ‘Grave of the Saint’s Servant’ (Jones 2006, 93).

The road Bóthar na Méisel is still pointed out in the landscape running towards the hermitage as is the site of the servant’s grave. The bóthar is not a made road rather a distinct weathering of the limestone and the name may possibly remember an earlier pilgrim route from the west.

1st edition Ordnance Survey map (1842) depicting the Boher na mias and the grave of St Mac Duagh’s Servant.

An early medieval bullaun stone is one of the earliest features at the site.

Bullaun stone at St Mac Duagh’s hermitage

There are no historical records to suggest pilgrimage occured at the site during the early or late medieval period. However pilgrim is seldom recorded during the early/late medieval period so the silence of the records cannot be seen as definitive evidence of pilgrim not taking place. St Colmán was a significant saint with a very strong cult in the region. Close to the church are two leachta (leacht singular), low, rectangular, drystone-faced cairn. This type of monument occurs at other early medieval ecclesiastical sites known to have been places of pilgrimage such as Innishmurray Co Sligo. Leacht seem to have had a variety of funtions some may have marked a special grave, such as that of the site’s founder saint, and others may have served as a focal point for outdoor services and others were penitianal stations. We known that the leachta at St Mac Duagh’s were used during the 19th century as penitiential stations. Ní Ghabhláin (1995, 73) notes that one of the leachta was built over the rubble on the medieval church suggesting that its construction may be post medieval. It could also represent the rebuilding of an earlier structure during this period.

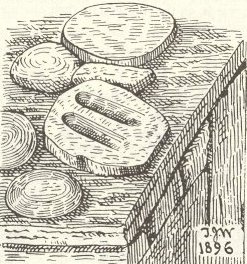

Westopp in the early 1900’s recorded a number of round stone on top of one of the leachta.

we find several of these stones and a flat slab with two parallel shallow flutings (each with one end rounded), lying on the altar.

Image of stones formerly located on on the leacht at St Mac Duagh Hermitage (Westropp 2000, 36).

Unfortunately the whereabouts of the stones are at present unknown but they may have functioned in the pilgrim rituals of post medieval pilgrims. Westropp noted

St. John’s altar at Killone ‘Abbey,’ and those at Kinallia and Ross, appear to be used only as a rude rosary to keep count of the prayers and ‘rounds’ offered at these shrines.

Another focus for pilgrims to the site, at least in the 19th century if not long before, was the holy well dedicated to St Colmán Mac Duagh, known as Tobermacduagh. The well is still an active place of pilgrimage and the water is believed to cure back ache and sore eyes.

The well is a natural spring encloused by a circular wall with a gap allowing access to the water. The gap/entrance to the well interior is covered by a large flat stone which acts as a lintel. The well is over shadowed by a tree covered in an eclectic mix of votive offerings.

The Ordnance Survey Letter’s for Clare (1839) state

Immediately to the east of Templemacduagh at Kinallia is Tobermacduagh, at which Stations are performed and a “Pattern” held on St. Mac Duagh’s Day, said to be last day of summer, but this must be an error, as St. Colman Mac Duagh’s Day is the 3rd of February.

and that

There are also here two altars or penitential Stations at which pilgrims perform their turrises or rounds on the “Pattern Day” or on any day they wish.

This short decription suggest pilgrims circled the leachta in prayer as part of the pilgrim rituals.

Westropp (2000, 36) writing in the early 1900’s recorded that

on the last day of summer rounds are performed at the two altars of the oratory of St Colman Mac Duagh at Kinallia.

Both reference to pilgrimage taking place on the last day of summer may impy that it was once a Lughnasa site.

Frost (1893) in The history and topography of the county of Clare, from the earliest times to the beginning of the 18th century records pilgrimage taking place on the 3rd of February.

The place is still visited by pilgrims on the Saint’s day, February 3rd.

This date coincides with the begining of Spring and the festival of Beltane. It is possible that the times of the pilgrimage changed from the site the Summer to Spring or that Frost was taking on board what the Ordnance Survey Letters had said and changing the date to correspond their thinking.

I’ve been told a communtiy pilgrimage still takes place here on the feast day of the saint 29th of October. I’m hoping to investigate this further.

The holy well is visted throughout the year. The tradition of tieing rags and other items to the tree beside the well is pretty recent. The practice also has a destructive effect on the holy well as people climb on the wall enclosing the well and loosen stones damaging the walls. Tony Kirby has written a very interesting report on the practive of votive offerings at the site and you can read this report by following the links embedded here and in reference section. The report notes other damage at the site such as graffiti carved on the church walls and on the rag tree caused by a minority of pilgrims and tourists.

As pilgrims and visitors to holy places like St Mac Duagh Hermitage we need to consider how our visits can impact the site and others like it. We should all avoid damaging walls by climbing on them, resist the urge to carve out names on stones and trees and if attaching offerings to trees use biodegradable materials and avoid plastic, wire etc items which could in the long-term damage the tree.

Reference

Frost, J. 1893. The history and topography of the county of Clare, from the earliest times tot he beginning of the 18th century. Dublin, Printed for the author by Sealy, Bryers & Walker.

Jones, C. 2006. The Burren and The Aran Islands. Exploring the Archaeology. Cork. The Collins Press.

Kirby, T. 2016 VOTIVE OFFERINGS DEPOSITION AT ST COLMAN MAC DUAGH’S HERMITAGE, EAGLE’S ROCK, KEELHILLA.Prepared for the Burren/Cliffs GeoparkLIFE project March 2016

Westropp, T. 188-1901. The Churches of County Clare, and the Origin of the Ecclesiastical Divisions in That County. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901), 6, 100-180. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20488773

Westropp, T. reprint 2000. Folklore of Clare: a folklore survey of County Clare and County Clare folk-tales and myth. Clasp Press.

Click to access rian-na-manach-a-guided-tour-of-ecclesiastical-treasures-in-co-clare-8938.pdf

Save