Doon holy well is one of the most popular wells in Co Donegal. The well

…..was established by a Lector O’Friel who is reputed to have lived in the Fahans area and had remarkable curative powers. When the locals asked him what they would do once he was gone from them, his answer was the creation of Doon Well. According to tradition, he was supposed to have fasted for 18 days and on each of these days he walked from Fahans to Doon a distance of some four miles. On the 18th day he blessed the well promising that if the people believed in the holy water then they would receive the same cures and blessings that he had imparted to them. According to local tradition it was a Fr. Gallagher in the 1880’s who blessed the well and he is still prayed for as part of the turas.

https://www.downmemorylane.me.uk/Donegal%20D1.htm

The schools collection record a similar origin story in the 1930s.

The well was founded by Father O’Friel about thirty years ago, and it was blessed by Father Gallagher. When any person goes to Doon well, they have to say one our father and one hail Mary for the intentions of these priests. It was people named Gallagher’s who put the shelter around it. When we go to Doon well, we have to go to the people that are in charge of it and get a penny ticket from which to say the prayers.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1083, Page 047 (Letterkenny, Co. Donegal).

Doon well is situated in the front yard of a farm house. The holy well is covered by a small stone walled rectangular structure, with a large flat flagstone roof. The area around the well is paved and a series of steps provide access to the interior of the well. The well and its surrounding are very well maintained.

There are two small rag trees beside the well. The trees are covered in a wide variety of offerings left by pilgrims. The offerings include religious medal, hair ties, rosary beads, religious statues and scapula. The volume of offerings show how popular the spot is still with pilgrims.

Doon holy well it is a living landscapes ever evolving. Its current vista was created in the early 2000s. This photo essay uses images of Doon holy well from the photographic collections in the National Library of Ireland (NLI) and the National Museums Northern Ireland (NMNI) to show how the well has changed over time and to provide a glimpse of how pilgrims experienced Doon well over a 100 years ago.

At the turn of the twentieth century the well was located in an open marshy landscape.

Doon well is situated in the parish of Kilmacrenan. It is situated in a green field by the roadside. It is a hilly rocky place, and there are a lot of hills and rocks around it. There is white and purple heather growing on the rocks, and people when they go to the well, go in search of the White heather, as it is very scarce around our district.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1083, Page 047 (Letterkenny, Co. Donegal)

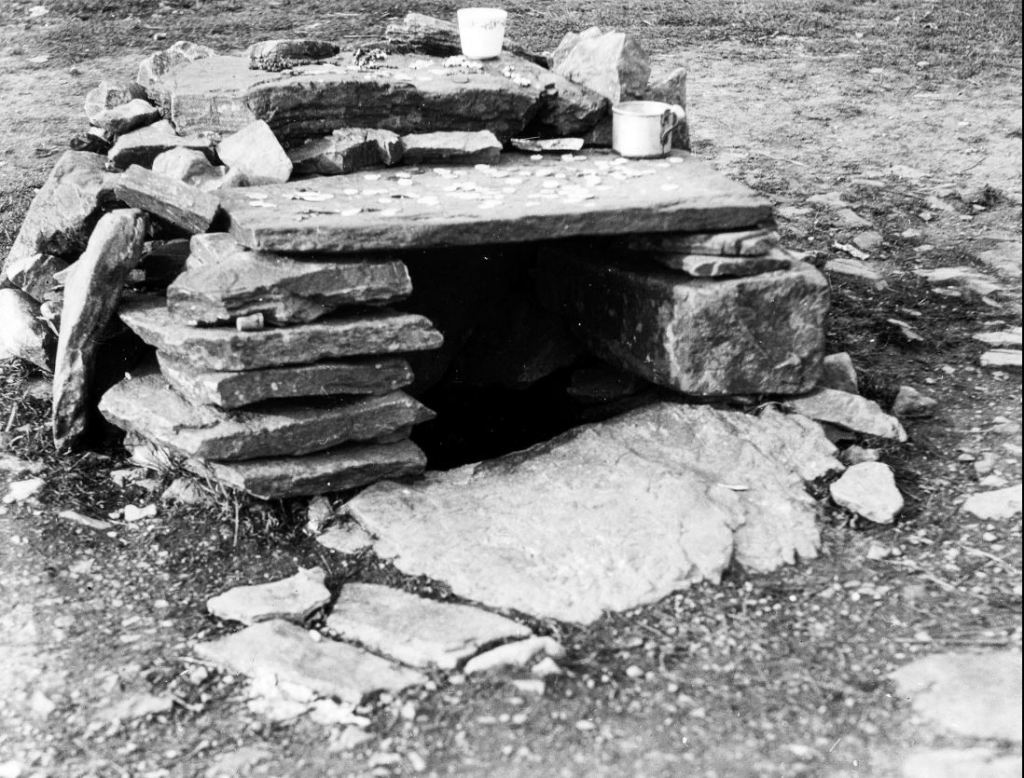

The well was originally an open natural spring. It was covered with stones to keep the waters clean some time in the 1800’s.

It is a long time since the well was first sheltered by stones which are built around it to keep the water clean and a large flat stone known as a flag was placed on top.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1083, Page 036

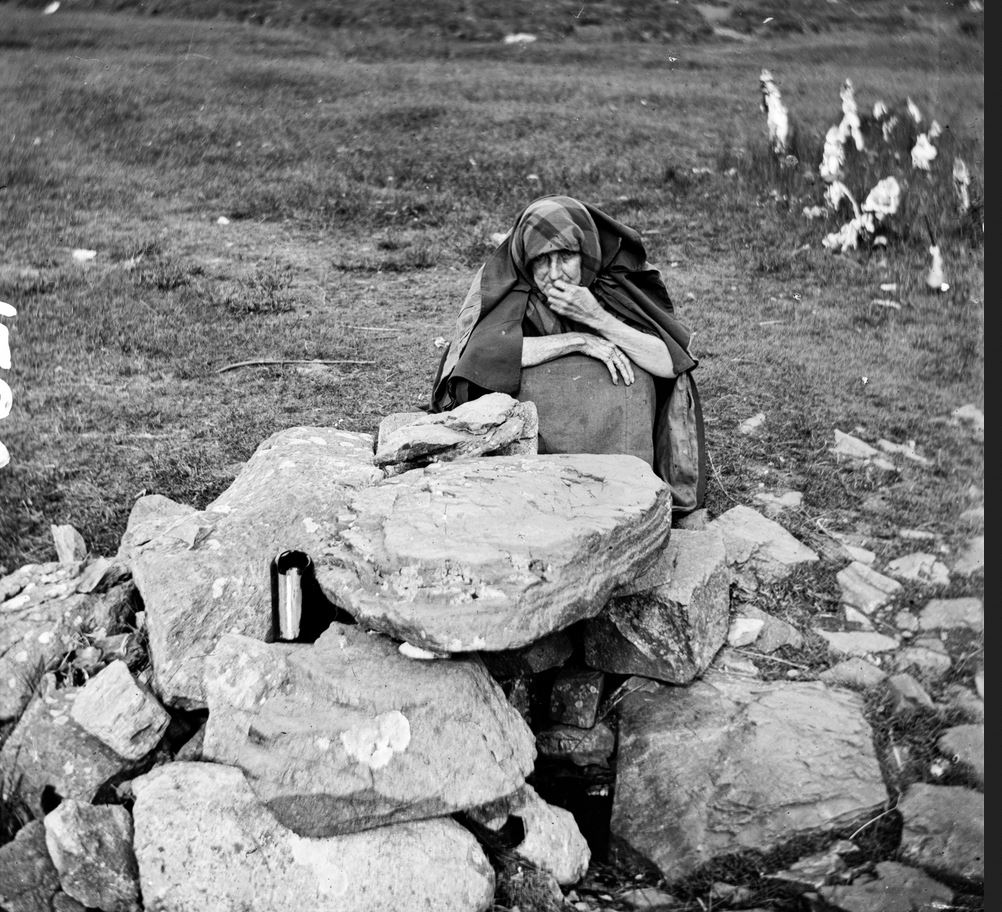

A photo of two women praying at the well from circa 1870-1890 shows the well covered by a collection of large stones stacked on top of each other.

Another early image of the well also in the National Library of Ireland (NLI) collections shows the well in a similar state. The photo show an elderly woman crouch in prayer beside the well. The woman’s expression is incredibly soulful and haunting.

In later images the well has a more formal covering, with a large flat flag stone used as a roof. A photo was taken by Robert French in the late nineteenth-early twentieth century and shows the well surrounded by low wall on three sides covered with a large flat flag stone. The walls are made up by irregular shaped stones of different sizes. The area surrounding the well is without grass pointing to continuous traffic of pilgrims, who made “rounds” of the well.

A photo in the NMNI collections, from the 1930s shows additional changes to the well superstructure. In the photo the superstructure has been extended and a second flat stone used as part of the roofing of the well.

Modern visitors may be surprised that the rag tree beside the well are a more recent addition to the landscape. In times past the well was surrounded by crutches and sticks covered in bandages and cloths. Rags were also tied to bushes close to the well.

In the past it was common for pilgrims who believed they had been healed to leave behind their crutches and bandages and rags at the the well. Interestingly when I visited Doon well in 2016 there were 2 crutches left at the rag trees.

A boy from the Ross’as was cured at Doon well. He was lying for seven years before that. It was his aunt that took him to Doon well at first. The first thing that a person notices at Doon well are the two new crutches that he left behind him when he was cured.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1054B, Page 09_056 (Meenagowan,Co. Donegal)

Lots of people were cured at that well. Crippled people used to come with crutches to the well and walk home without them, cured.

Along with reciting set prayers, pilgrims in search of healing washed their limbs in the wells waters.

The people drink it and wash the affected parts with it. They also take bottles of water home with them. You have to wash your feet in moss water and lift the water while still on the bare feet.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1085, Page 126-7.

The tradition of leaving behind offerings at the well is a long standing tradition. In the 1930s pilgrims left handkerchiefs and strips of cloth along with religious medals (The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1085, Page 126 (Woodland, Co. Donegal).

It is the custom always to leave something behind you at the well, some leave a hanky, others leave little things belonging to themselves. People take the water home with them from Doon Well.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1076, Page 431

Doon holy well is visited throughout the year. Two main vigils are held here, one on New Year’s Eve and the other on May Eve.

People go to Doon well on St Swithin’s day, St Patricks day, and Easter Sunday.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1084, Page 036

They very often go on any week day, but usually on a Saturday or a Sunday.

A plaque at the well details the prayers made by modern pilgrims. Modern pilgrims say five Our Father and Hail Mary and the Apostles Creed for their intention. These prayers are repeated if the pilgrim decides to take water from the well. Pilgrims also say an Our Father and Hail Mary for Father O’Friel and also an Our Father and Hail Mary for Father Gallagher who blessed the well. An additional Our Father and Hail Mary is recited for the person who put the shelter around the well. Pilgrims throughout the decades have made their prayers in their barefeet while walking in circles around the well.

There are many photos from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with pilgrims making their prayer and barefoot at the well.

In the 1930s the pilgrim rituals are described as follows

To make a pilgrimage correctly one has to fasting and when he comes in sight of the well their shoes must be taken off as it is believed the ground is blessed. He washes his feet in the water, which is to be got all around. Then the prayers are proceeded with Five Our Fathers, Give Hail Mary’s, and Five Glorias in honour of Father O Gallagher and Father O Friel, and the same for the person who sheltered the Holy Well. Also a creed for every bottle of Holy water lifted.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 1083, Page 036

I hope this post inspires some of you to visit Doon well, its such an interesting place. Its also located close to Doon Rock the former inauguration site of the O’Donnells. The Voices from the Dawn blog has a very interesting blog post on the Rock of Doon.

References

https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000560011

http://hiddendonegal.town.ie/page/holywellsandabbey

https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000317831