Clonmore, Co Carlow is located 3½ miles south of Hacketstown and 9 miles east of Tullow in the north-east corner of the county, close to the Wicklow border. The modern village developed around the site of an early medieval ecclesiastical settlement.

View of St Johns Church of Ireland Church Clonmore and road that runs through the monastic site.

Clonmore was founded some time in the sixth century, by St Maodhóg also known as ‘Mogue’. The saint was a member of the Ua Dúnlaing tribe who were the ancestors of the Uí Dhúnlainge Kings of Leinster. He is not the same as St Maodhóg of Ferns and the two are often confused because they had the same name. Maodhóg of Clonmore was mentioned with other Leinster saints in poem attributed to St Moling as the ‘golden vessel’ (Ó’Riain, 2011 431). His feast day seems to 11th of April (ibid , 432).

Little is know about the early history of Clonmore. The deaths of abbots of Clonmore are recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters in the years 771, 877, 886, 919, 920 and 972 . The annals also record that the monastery was burned in 774, attacked by the Vikings in 834 and 835 and in 1040 by Diarmait mac Mael-na-mBó.

The site appears to have been a place of pilgrimage during the early medieval period. An early medieval poem written by Brocán Cráibhtheach tells that Clonmore housed a vast collection of relics of the saints of Ireland. The collection included the little finger of St Maodhóg cut from the saint while alive at the request of Onchú a saintly relic collector who amassed a vast collection of relics of Irish saints. St Maodhóg agreed to part with his finger on the condition Onchú’s collection of relics remained at Clonmore. Onchú was also said to have been buried here at Clonmore. His feast day was recorded as the 8th of February. Interestingly local tradition identifies the area where Onchú was supposed to be buried in Clonmore graveyard. Clonmore was also associated with St Fíonán Lobhar.

The site of Maodhóg’s monastery is believed to be located on the west side of the village beside a small stream. A modern road runs through the centre. A historic graveyard containing a large collection of early medieval crosses is found on the south site of the road. St John’s Church of Ireland church and churchyard is located on the north side of the road. There are no surviving traces of the monastic enclousre or buildings.

St John’s church was built c. 1812 it is surrounded by a triangular shaped graveyard. To the west of the church is a large solid ringed granite high cross known as ‘St. Mogue’s Cross’.

South Face of St Mogue’s Cross

North face of St Mogue’s Cross

Killanin & Dugnan (1967, 304) mention an ‘ancient stone tough’ in the vicinity of the cross but I on my visit I could not find it and I hope it has not been stolen.

The historic graveyard on the south side of the road is a rectangular area enclosed by a wall and it contains a large number of early medieval cross slabs. Some of the crossslabs are set in lines among rows of 18th and 19th century gravestones. According to Harbison (1991, 179), in 1975 all the loose stones crosses and cross slabs were gathered up by a local work party under the supervision of the then County Engineer, Michael O’Malley, and set upright in neat rows within a small paved area enclosed by kerbing at the north-western corner of the graveyard.

Paved area containing early medieval cross slabs at the north-western corner of Clonmore graveyard.

The head of second high cross is found in this paved area and the shaft and base are located a few meters to the northeast. According to Ryan in the History and Antiquities of the County of Carlow local people in the 19th century believed the cross had been destroyed by Cromwell.

West face of head of high cross

East face of the head of high cross

Shaft and base of high cross along with fragment of the shaft

Harbison (1991) has identified 24 early medieval cross slabs in the graveyard. The crosses include Greek crosses with expanded terminals incised or sunk into the surface, Latin crosses incised and carved in relief (by far in the majority) and 4 ringed crosses.

An ogham stone is also found in the graveyard Harbison believes it to be located in its original position and noted that

Eddie McDonald has pointed out to me that local tradition places the tomb of St Onchuo between it and the South Cross less than 2m away from it (Harbison 1991, 177).

The stone has been analysised by the wonderful Oghan in 3D project who state that

Faint traces of Ogham lettering on the SE angle … much worn and clogged with lichen’. ‘[The first two strokes of] R are lost by the fracture, and the I is broken and hard to recognise’ (Macalister 1945, 18). With the naked eye alone it is difficult to be certain that any inscription survives today. On the 3D model it is possible to make out faint traces of ogham. The 3D data was analysed by Dr Thierry Daubos of the Protecting the Inscribed Stones of Ireland project in Galway in an attempt to clarify the text (3D Analysis). Unfortunately, the scores and notches are too worn for any certainty except to confirm the presence of an ogham inscription. Macalister’s E is possible but the N may be an S and his final I looks more like a consonant, possibly C, with scores to the left of the stemline. Nevertheless, Macalister’s reading is given below as certainty is no longer achievable and it is possible that the inscription was less worn when he read it.

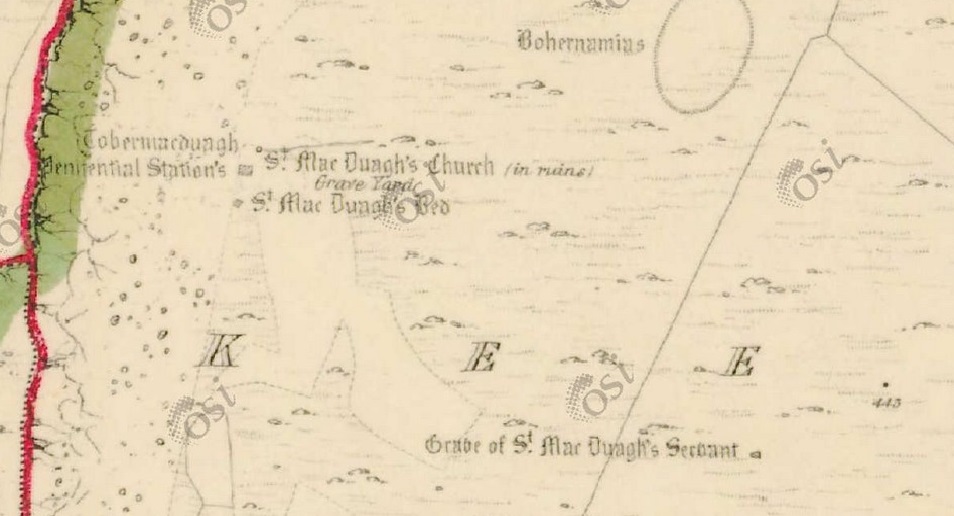

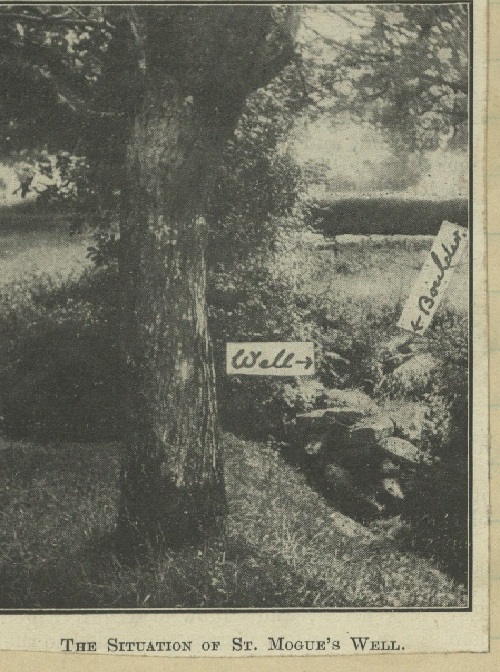

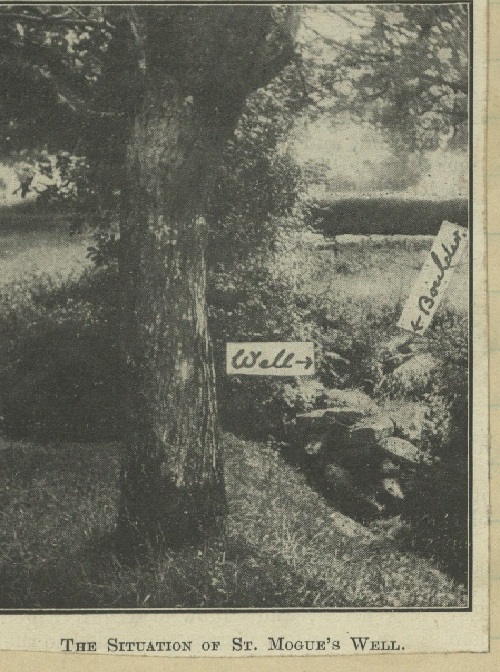

During the 18th and early 19th century St Mogue’s (Maodhóg) holy well was the focus of pilgrimage. The well is located a few meters from the high cross beside St Johns Church ,on the north side of the road the bisects the monastic site, Today the holy well sits within a landscaped community prayer garden. In times past the well was the site of a pattern on the 31st of January/1st February, the same day as the feast of the saints name sake St Maodhóg of Ferns, during the 18th century. The Ordnance Survey Name books for Carlow written in 1839, describe the well as

a small well with a stream running therefrom. A patron used to be held here on Saint Mogue’s day, the 1st of February but has been discontinued 30 years past.

St Mogue’s Well Clonmore

Interior of St Mogue’s holy well Clonmore

St Mogue’s holy well and prayer garden Clonmore

Clonmore prayer garden

The Antiquities and History of Cluain-Mor-Maedhoc published in 1862

it was until recently resorted to by peasantry for miles around for the cure of many diseases, it is now nearly unknown and neglected, and suffered to choke up with grass and weeds.

The Schools Collections in 1939 stated that

The well is resorted to at the present time for the cure of sore eyes, warts or any skin growths -even for cancer (Clonmore School The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0909, Page 165).

For cures to be affective, water was taken from the well and applied to the hurt

This has to be done on three successive Fridays according to some; others say that it may be done on any day (Clonmore School The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0909, Page 165).

The earlier descriptions of the well make no mention of a well house and a photo in the Schools Collections from the 1939 shows the well as being open and enclosed by a low stone wall with the bullaun stone known as the wart stone sitting on the side of the wall surrounding the well.

St Mogue’s well taken The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0909, Page 166

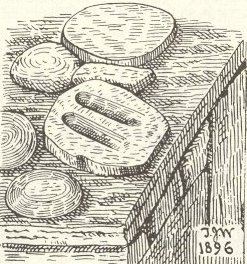

Today the well is covered by a well house and the small bullaun stone/wart stone is found within the house ( built post 1930). To cure warts it was said the pilgrim needed to take from the well and pour it into the hallow of the stone and then apply to the afflicted area (O’Toole 1933, 114; Clonmore School The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0909, Page 111).

Directly opposite the well and prayer garden in the field on the south side of the road is a large four basin bullaun stone. The stone was once located at the centre of the field but was moved to the easten edge during land improvements and now sits at side of stream known as Church Brook.

Bullaun stone at Clonmore

Four depressions on surface of bullaun stone at Clonmore

Bullaun basins on stone at Clonmore

The stone is a large granite boulder about 2m in lenght with three deep depression about 30cm in diameter , the fourth is a shallow depression.

According to folklore the stone was originally located at the monastic site but following raids by the Danes( Vikings) it jumped three times. In the first jump it landed at the site of the St Mogue’s holy well and causes the well spring up, the stone then jumped to the castles and from here to its former location in the field.

At that time all the land around there was poor and wet but when it lighted there it said:-

“Here I will stay till the destruction of the world and I vow that his farm will turn into fertile land, the most fertile in the parish of Clonmore and no one will interfere with me, and no grass will grow over me and I will be here till the end of time”. (Clonmore School The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0909, Page 111)

Apart from the early medieval remains Clonmore also has a large Anglo-Norman Motte and a stunning 13th century castle.

Clonmore castle located a short distance from the site of Clonmore monastery

References

Brindley, A.L. and Kilfeather, A. 1993 Archaeological Inventory of County Carlow. Dublin. Stationery Office.

McCall, J. 1862. The Antiquities and History of Cluain-Mor-Maedhoc. Dublin : O’Toole

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, U.C.D Schoolbook vol 0909, Clonmore (1939)

Harbison, P. 1991. ‘Early Christian Antiquities at Clonmore, Co. Carlow’ Proceeding of the Royal Irish Academy Vol.91 C, 177-200.

Killanin, M. & Duignan, M. 1967. The Shell guide to Ireland. London: Ebury Press.

Macalister, R.A.S. 1945 Corpus inscriptionum insularum celticarum. Dublin. Stationery Office.

O’Toole, E. 1933. ‘The Holy Wells of County ‘, Béaloideas, Iml. 4, Uimh 2 pp. 107-133.

Ordnance Survey Letters for Co Carlow. http://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/digital-book-collection/digital-books-by-subject/ordnance-survey-of-irelan/

Ryan, J. 1833. The history and antiquities of the county of Carlow. Dublin: Richard Moore Tims.

White, N. 2016. ‘CW009-028021 , Ogham Stone Clonmore’ http://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/( accessed 24/01/2018).