Saint Gobnait: first impressions

I first came across St Gobnait when I wandered in to the Honan Chapel around 14 years ago. The Honan chapel is very beautiful church located on the campus of University College Cork. It has many splendid stained glass windows by Harry Clarke, who in my opinion was Ireland’s finest stain glass artist.

As I wandered around the chapel I looked up at one of the many windows which depicted various Irish saints and there was Gobnait. Her window is one of the most beautiful depictions of a saint I had ever seen. The window shows Gobnait of Baile Bhúirne/Ballyvourney adorned in blue robes and surrounded by bees, at her feet are two men with fearful expressions. My curiosity immediately demanded that I find out who this saint was, where she came from and most importantly what was the connection with the bees?

Who was Gobnait and where did she come from?

Much of what we know about Gobnait comes from folklore. Unlike many other Irish saints, Gobnait’s life story was not written down during the medieval period. Tradition and links with St Abban (also associated with Ballyvourney) suggests she lived during the 6th century. Today the main centres of devotion to Gobnait are on Inis Oírr/Inisheer ( one of the Aran Islands), Dún Chaoin in West Kerry, Kilshanning, Co. Cork and Baile Bhúirne/Ballyvourney near the Cork/Kerry border, where the local people venerate the saint on her feast day, the 11th of February. Evidence of the saint’s cult is also found in the dedications of churches and holy wells in the counties of Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Waterford.

There are two folk versions of the saints life. One tells us that Gobnait was born in Co Clare and due to a family feud fled of to the island of Inisheer where she founded a church. One day an angel appeared to her and told her to head inland and to find the place of her resurrection. She was told she would know this spot as it would be marked by the presence of 9 white deer. She travel south in search of this place and her many stops are marked by churches and holy wells dedicated to her, such as the medieval church at Kilgobnet, Co Waterford.

At various stages of her journey Gobnait met with white deer of varying numbers but it was only when she reached Ballyvourney that she found the nine deer grazing and it was here she ended of her journey. In a Kerry version of her life, Gobnait was said to be the daughter of a pirate who came ashore at Fionntraigh (Ventry, Co. Kerry). Once ashore an angel appeared to her and told her to go forth and search for the site of her resurrection and to travel on until she saw nine white deer grazing, which she did in Ballyvourney.

I will post more in the coming months about Gobnait’s journey around Ireland and the other sites associated with her. This post will focus on the evidence of pilgrimage at Ballyvourney.

Metal working and bees

Gobnait was likely the patron saint of iron workers. The hypocoristic (pet name) form of her name Gobba come from Gabha which means smith. Excavations St Gobnait’s House/Kitchen at her shrine in Ballyvourney in the 1950’s, prior to the erection of the modern statue of St Gobnait, revealed evidence of iron working (smithing and smelting).

Gobnait was also the patron saint of bee keepers and kept her own bees. There are a number of legend in which she unleashes her bees to attack enemies. In one story soldiers came to Ballyvourney and stole livestock, as they left the village the saint let loose her honey-bees upon them. Another version of this tale has a band of robbers stealing her cattle and she sends her bees after them and they promptly return the cattle. It is this legend that inspired the Harry Clarke window. Many modern depictions of the saint associate her with bees such as the statue at her shrine in Ballyvourney by Séamus Murphy.

St Gobnait in the rain. Statue of St Gobnait created by Seamus Murphy in the 1950s.

Medieval Pilgrimage at Ballyvourney

Gobnait is not the only saint associated with Ballyvourney. St Abban had established a monastery here prior to her arrival. Abban gave her land and helped she established a nunnery here. The traditional site of Gobnait’s nunnery is the old graveyard and medieval parish church known as Teampall Ghobhatan ( the church of Gobnait). I will come back to St Abban and his links to Ballyvourney in another post.

There is little evidence to suggest when pilgrims first began to come here. Unfortunately the archaeological and historical sources tell us nothing about pilgrimage prior to the 17th century. Given the popularity of the saints cult in the 17th century it is likely pilgrimage likely began many centuries prior to this date.

The silence of the historical and archaeological record concerning pilgrimage at Ballyvourney, should not be seen as evidence that pilgrimage was not taking place in the early or later medieval period. Pilgrimage is seldom mentioned in the historical records and the act of pilgrimages in most cases leaves little physical trace behind.

The earliest written reference to pilgrimage at Ballyvourney dates to the early 1600’s. In 1601 Pope Clement VIII granted a special indulgence of 10 years to those who, on Gobnait’s feast day, visited the parish church, went to Confession and Communion and who prayed for peace among ‘Christian princes’ , expulsion of heresy and the exaltation of the church’. It is clear from this and other 17th century references, such as the poetry of Dáibhidh Ó Bruidar, the writings of Don Philip Ó Súilleabháin and Seathrún Céitinn, that Gobnait’s cult was strong and popular during this period.

In 1603 Donal Cam Ó Súilleabháin during his flight from Béara stopped at Ballyvourney with his men to pray at Gobnait’s shrine, to offer gifts and to ask for her protection. The importance of Gobnait’s cult is also attested by the visited of the Papal Nunico Rinuccini in 1645 (Ó hÉaluighthe 1958, 47).

Devotion to Gobnait is again mentioned in the writings of Sir Richard Cox in 1687, who stated

Ballyvorney, a small village, considerable only for some holy relick (I think of Gobbonett) which does many cures and other miracles, and therefore there is great resort of pilgrims thither.

The relic described by Cox is a small 13th century medieval statue of St Gobnait, now in the care of the parish priest of Ballyvourney.

Medieval statue of St Gobnait

Gobnait’s statue was again mentioned in 1731 when it is noted that

this Parish is remarkable for the superstition paid to Guibnet ‘s image on Gubinet’s Day.

The literary sources suggest that the hereditary keepers of the shrine and relics of Gobnait (the statue) were the O’ Hierlihys family. Many of the relics of Irish saints survived the reformation as they were kept by individual families and passed down from generation to generation. These families were descendants of the family of stewards, or airchinnaigh, who controlled monastic lands and were often remunerated with a specific plot of land and fees when the relic was used. During the 18th & 19th century many of these families fell on hard times and sold the relics some have been lost but thankfully many are now in the National Museum of Ireland. The statue of Gobnait continued to be cared for by the O’Herlihy family until 1843 when the statue was given into the care of the parish priest and it remains in the care to church of Ballyvourney to this day.

John Richardson, a protestant gentleman with a low opinion of pilgrimage, gives an account of the 18th century pilgrimage at Ballyvourney in his book The Great Folly of Pilgrimage. His account suggests that devotion was focused on the aforementioned statue of St Gobnait and makes no mention to any of the stations visited by modern pilgrims.

An Image of Wood, about two Foot high, carves and painted like a Women, is kept in the Parish of Ballyvourney, in the Diocese of Cloyne, and the County of Cork; it is called Gubinet. The pilgrims resort to it twice a year, viz on Valintine’s Eve and on Whitsun Thursday…. it is set up for adoration on the old ruinous walls of the church. They go around the image trice on their knees saying a certain number of Paters, Aves and Credos. Then following prayer in Irish ‘A Gubinet, tabhair slan aon Mbliathan shin, agus sábháil shin o gach geine agus sórd Egruas, go speicialta on Bholgach’ and they conclude with kissing the idol and making an offer to it every one according to his ability, which generally amounts in the whole to 5 or 6 pounds. The image is kept by one of the family of the O’ Herlihy’s and when anyone is sick of the small-pox, they send for it and scarifice a sheep to it, and wrap the skin about the sick person, and the family eat the sheep. But the Idol hath now much lost its Reputation, because two of the O Herlihys died lately of the Small pox. The Lord Bishop of Cloyne was pleased to favour me with the narrative of his rank idolatory, to suppress which he hath taken very proper and effectual methods (Richardson 1723, 70).

He goes on to say

Pilgrims kissed the statue, rubbed aching limbs to it, tied handkerchiefs about its neck, to be worn afterwards as a preventative against sickness (Richardson 1723, 71).

Richardson’s writings are very anti Catholic and written at a time when pilgrim was viewed as superstitious and backward by the established church, despite his negative tone his writing provides one of the most detailed of the early accounts of pilgrimage at Ballyvourney. During the 18th and 19th century pilgrimage was not just under pressure from the established church, many Irish pilgrimages were suppressed by the Catholic clergy but thankfully the efforts of the then Bishop of Cloyne to eradicate the pilgrimage at Ballyvourney were in vain.

The modern pilgrimage at Ballyvourney on the saint’s feast day

I have been to Ballyvourney on a number of occasions, but this year was the first time I attended a pilgrimage. I arrived in the village around 10.30 am. I was told by some people i meet that was mass in honour of Gobnait, would be said at 11.30am & 16.00pm and that a rosary would be said at the shrine at 15.00 pm. I was also informed that people visit the statue of Gobnait and the shrine & holy well to do their ’rounds’ (pilgrim prayer) throughout the day .

I headed first to the church to see the medieval statue of St Gobnait. The statue is a treasure possession of the parish of Ballyvourney and it is fascinating to think that it has survived here in this parish since the 13th or 14th century. Made of oak, it is approximately 27 inches/ 68 cm tall. The back is hollowed out from the shoulder to the feet. The face is now very worn and traces of paint can be seen on the front of the statue. The folds of the saint’s dress and a belt are still visible. The feature of her face are now undiscernible but the details of her hands (one hand is raised to her chest and the other by her side) are clearly visible.

St Gobnait’s Statue, photo showing detail of hands & robe

On the saint’s feast day the statue is displayed within the church. On the occasion of my visit it was placed on a small table in the church in front of the altar. A table with a large jar of colourful ribbons, key rings and booklets about Gobnait (all for sale) was located a few meters away from the medieval statue in front of a modern plaster statue of the saint. People queued up and purchased fistful of ribbons and formed orderly lines to approach the medieval statue. The pilgrims armed with their ribbons (which they had brought with them or just purchased) , were no ready to perform the ritual called St Gobnait’s measure. This is a practice were pilgrims use the ribbons to ‘measure’ the statue.

Pilgrim’s taking ‘St Gobnait’s measure’ after mass in Ballyvourney church.

The ribbon(s) is held along the length of the statue and then wrapped around the neck, then the waist and finally the feet of the statue. Some pilgrims make the sign of the cross when this is done, others pick up the statue and kiss it, while others bless themselves with the statue. The ribbon or in most cases ribbons are then brought home and used to ward off and to cure sickness. Farmers often placed the ribbons in outhouses where there is livestock. As I sat in the church waiting for mass there was a constant line of people waiting to get to the statue. The scene reminded me of Richardson’s description of pilgrims in 1723, which tells of pilgrims tieing handkerchief to the statue and then wearing them about the neck as a preventative against illness. It was fascinating to see that modern pilgrims are interact with the statue in much the same manner as their ancestors almost 300 years before. The church soon filled to capacity and a mass was said in Irish. There was a mix of people from within and outside the parish in attendance. Many people had travelled some distance to get here and I heard one man say he came that morning with his son from Killorglin in Co Kerry.

After mass a new group of people lined up to visit the statue with their ribbons. I was told people would come throughout the day to visit the statue but the main burst of activity focused around mass times. When I passed by the church later at 16.15 the car park was again chock-a-block with cars.

Pilgrim stations at St Gobnait’s shrine.

A short distance from the village is St Gobnait’s shrine, the other focus of devotion for pilgrims to Ballyvourney. As I mentioned above St Gobnait’s shrine is the traditionally held to be the site of St Gobnait’s nunnery and the burial-place of the saint. Throughout the year it attracts pilgrims on a daily basis. The main peaks in pilgrimage are Whitsun, the feast of St Gobnait, on the 11th of February and an open air mass in July.

The landscape of the shrine is divided in two with St Gobnait’s house, holy well and statue separated from the other stations by a modern road. During the course of my visit I meet another blogger Richard Scriven (Geography UCC) who is currently doing PhD research on the modern pilgrimage at Ballyvourney. For more details of Richard’s research check out his blog http://liminalentwinings.com/.

The day was very cold with light to heavy showers but during the time I was here there was a constant stream of pilgrims. Most pilgrims were in small groups of two or three and many were alone. A small crowd gathered at 15.00, for the rosary , in the area beside St Gobnait’s house. Many of the people here who attended the rosary left afterwards perhaps to catch the 16.00 mass, while a small group remained to do the stations.

Pilgrim’s hiding from the rain during the recitation of the rosary at Ballyvourney

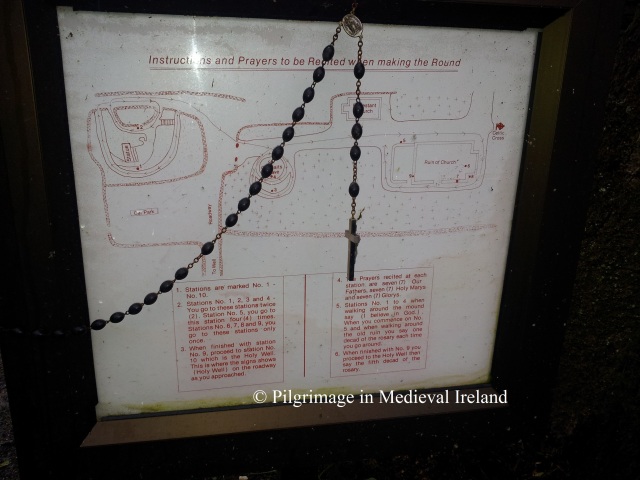

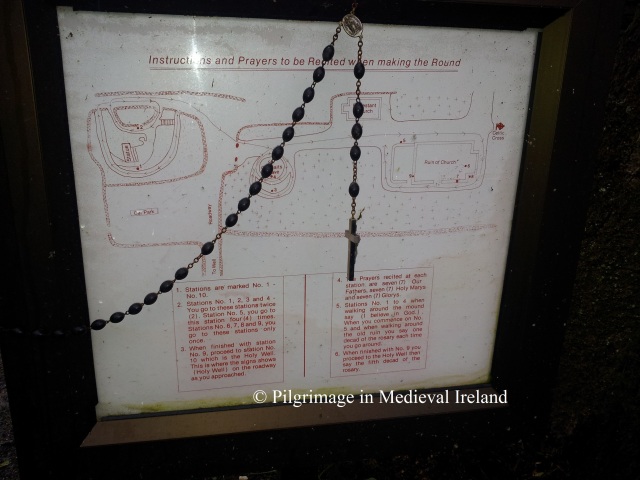

Modern information boards are found beside all the pilgrim stations and detail the required prayers for each stations.

One of the modern notice boards located at the shrine.

The following details of the rounds is taken from the book Saint Gobnait of Ballyvourney by Bernie Donoghue Murphy written in c. 2007.

Pilgrimage begins in front of the statue of Gobnait. The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria, then walks clockwise ‘ ar deiseal’ around the outer path (around the periphery of the site) reciting the Apostles Creed. The practice of pilgrims walking in a clockwise circuit can be traced back to early medieval times and continued in post medieval and modern times.

Pilgrims beginning their round before the modern statue of St Gobnait.

At St Gobnait’s House (station 2) the pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria. The pilgrim walks clockwise around the station reciting the apostles creed. I also saw people go inside the hut and walk clockwise around the interior and finish by marking a modern pillar with a cross.

Pilgrim within St Gobnait’s house marking the centre pillar with a cross.

This station was in ruins 1950s. It was restored following an excavation of the site by M. J. O’Kelly and rebuilt to its current state. The results of this excavation suggests the structure was used for craft working in the early medieval period. Large amounts of slag (the waste product of iron smelting), a crucible and other artifacts connected with iron working were recovered. Two bullaun stones (stones with man-made depressions), artifacts which many scholars believe were used to grind metal ores are found close by at the site of Gobnait’s grave.

Pilgrim praying at St Gobnait’s house (Ó hÉaluighthe 1958, Pl. 2)

Modern pilgrims have marked stones around the shrine with crosses as part of their prayers. The two entrance stones to St Gobnait’s house are marked by crosses, as are the modern cylinder shaped pillars within the hut and various stone in St Gobnaits church. This practice is seen at other pilgrim sites such as St Declan’s well at Ardmore. Such activity dates to post medieval and modern times. Small pebbles are left on top of these stone for pilgrims to incise the sign of the cross.

Crosses marked on the top of the modern pillar.

Having finished the prayers at station 2 , the pilgrim goes to the near by holy well , one of two wells associated with Gobnait at the shrine. The pilgrim then kneels down and drinks some water from the holy well.

Holy well beside St Gobnait’s house.

The remaining stations are found within the old graveyard. The pilgrim then crosses the road and enters the old graveyard.

Crosses etched on the modern styles

Station 3 & 4 are located beside each other, close to the main entrance to the graveyard. At station 3 the pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria. The pilgrim walks twice clockwise around the this station ( station 4 is at the centre of this path) reciting the apostles creed.

Pilgrims praying at Station 3 & 4.

Station 4 is a sod-covered mound of loosely packed stones (4m N-S; 5.6m E-W; H 1.3m) known as St Gobnait’s grave. The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria. The pilgrim then walks twice clockwise around this station reciting the apostles creed.

Station 4 St Gobnait’s grave.

On top of the mound is a large flat slab which pilgrims have incised with a cross. A small pebble is left beside the cross. This station is very colourful and eye catching. Pilgrims have left behind votive offerings such as holy statues, medals, rosary beads & crucifixes.

Cross incised by pilgrims on slab on top of St Gobnait’s grave.

From here the pilgrim walks past the 19th century Church of Ireland to Station 5, located at the corner of the old church. The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria. The pilgrim then walks around St Gobnait’s church 4 times, reciting at each circuit, one decade of the Rosary.

Pilgrim’s doing rounds of the church.

The pilgrim then enters the interior of the church. Station 6 is located at the east gable of the church. The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria .

Station 6 in the interior of the church.

Modern pilgrims have left there mark within the church. There are statues placed in putlog holes ( small square holes used to hold wooden beams, used in the initial building of the church) some of the stone in the fabric of the church and two 19th century grave stones have had crosses incised on them.

The pilgrim then moves on to station 7, located at the window at east end of the south wall of the church. A rectangular recess (cupboard) has been filled over the years by pilgrims with statues and beads and other religious memorabilia. The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria.

Station 7

On completion of prayers the pilgrim reaches out through the window and makes the sign of the cross above the top lintel on a piece of medieval sculpture known as Sheela-na -gig. Sheela are figurative carvings of naked women, usually bald and emaciated, with lug ears, squatting and pulling apart their vulva. These carvings are found many medieval churches, sometimes castle sites in Ireland and England. There is much uncertainty as to their original function some think, they were used to ward off evil, warn against lust or even fertility figure.

Window with Sheela-na-gig

The pilgrim then moves outside of the church to station 8, which is known as the priest’s grave. The grave marks the burial of Fr Daniel O’Herlihy was buried here in 1637. The pilgrim then recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria at this station.

Station 8, the priest’s grave

Station 9 is at the southwest corner of the west gable of the church. The focus of devotion is a polished agate stone ball, call the bulla. The ball is located in a rectangular recess and is renowned for its healing power. The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria. Some pilgrims had left a religious medals and a piece of paper probably with a petition to the saint beside the ball.

Station 9 the polished agate ball surrounded by votive offerings.

There is a folktale associated the with the stone. Legend has it an invader decided to build a castle in the area. Gobnait could see the castle walls from her church. Throwing the bulla at the castle she razed the castle walls to the ground. The stone then miraculously returned to the saints hand. Each time the walls of the castle were rebuilt the saint would knock them down again with the bulla. Finally the invaders gave up and move away.

To complete the pilgrimage the pilgrim walks down the road to St Gobnait’s well (Station 10). The pilgrim recites 7 Our Fathers, 7 Hail Mary’s and 7 Gloria, one decade of the rosary and drinks the water from the well.

St Gobnait’s well

Like many holy wells in Ireland St Gobnait’s well is associate with a rag tree and there is a tradition of leaving votive offerings at this tree. Below is a photo of the tree taken when I last visited here in 2006, as you can see is covered rags and bead and tokens left be pilgrims. I think it looks quiet lovely. Since my last visit most of these offering have been removed but a few are still to be found.

Tree beside St Gobnait’s well taken in 2006.

I came across another book called Saint Gobnait of Ballyvourney by Eilís Uí Dháiligh written in 1983. This book notes that many pilgrims begin there stations with the traditional prayer

Go mbeannaí Dia Dhuit, a Ghobnait Naofa,

Go mbeannaí Muire faoi mar a bheannaím féin dhuit.

Is chughatsa a thána ag gearán mo scéal leat,

Go dtabharfá leigheas i gcuntais Dé dom.

May God and Mary bless you,

O Holy Gobnait, I bless you too,

and come to you with my complaint.

Please cure me for God’s sake.

She also notes the traditional finishing prayer is

A Ghobnait an dúchais

do bhiodh i mBaile Mhuirne

Go dtaga tú chugamsa

le d’chabhair is le d’ chúnamh

(O St Gobnait of Ballyvourney, come to my aid).

Uí Dháiligh gives instructions for the pilgrimage as follows (taken directly from her book pages 25-26).

There are five Stations or Ulacha and each has a particular significance.

I The First Station or Ula Uachtarach is the site of Gobnait’s House. (Stop 1 & 2).

II The Second Station or Ula láir is her grave (stop 3 & 4).

III The Third Station brings us to her Church (stops 5 & 6).

At each of the three stations the pilgrim walks ar deiseal, that is clockwise, and prays. The customary practice is to say seven Paters; seven Aves; and either seven Glorias or the Apostles’ Creed at the outer ring of each Station which is traversed twice. The same is repeated around the inner circles twenty-eight Paters; twenty-eight Aves; and either twenty-eight Glorias or four Creeds in all.

Pilgrim praying at Station 5 and a group of pilgrims praying at Station 9 the bulla stone

IV The Fourth Station (Stops 7 & 8) is inside the church where one pater; one Ave; and either one Gloria or one Creed is said. The pilgrim pauses at the south window in honour of the effigy over the window head through by some to be an old image of Gobnait herself.

V The Fifth Station consists of a visit to the Priest’s Grave which lies outside the right corner of the East Gable, where one pater; one Ave, and one Creed are said (stop 9); a visit to the bulla in the south corner of the west gable (Stop 10) and the journey to the well (Stop 11). The pilgrim goes down the main road a little distance and enters the grove where he will find the old Well. Here he says one Pater, one Ave, and one final creed. He drinks the water and says a final prayer.

Cups and statues left on top of St Gobnait’s well.

Conclusion

Despite the lack of evidence for pilgirmage in the medieval period, I have no doubt that pilgrims were coming to Ballyvourney from an early date. Gobnait’s reputation as a healer and miracle worker would have attracted pilgrims from the immediate locality and further afield. We can never know how medieval pilgrims interacted with the shrine, but the pilgrim rituals would not have been static and would have constantly evolved as evident from the slight variation of the accounts of the modern stations described above. The medieval pilgrims to Ballyvourney like those in the 17th , 18th century would have come here for much the same reasons as modern pilgrims, to ask for help from the saint and in search of healing. Above all it is the devotion to Gobnait through the little wooden statue that links the people of Ballyvourney with their medieval forefathers.

© Louise Nugent 2013

References

Chaomhánach, E. ”The Bee, its Keeper and Produce, in Irish and other Folk Traditions’. Department of Irish Folklore.http://www.ucd.ie/pages/99/articles/chaomh.pdf accessed 8/07/2012.

Power, D. 1997. Archaeological Inventory of County Cork: Mid Cork v. 3. Dublin: Stationary Office.

Henry, F. (1952) The decorated stones at Ballyvourney, Co. Cork. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 57, 41-42.

MacLeod, C. 1946. ‘Mediaeval figure sculpture in Ireland’ JRSAI Vol. LXXVI, Part II.

Harris, D. 1938. ‘Saint Gobnet, Abbess of Ballyvourney’, JRSAI Vol. LXVIII, 272-277.

Ó’ h-Éaluighthe, M. A. 1958. ‘St. Gobnet of Ballyvourney’, JCHAS Vol. LVII, 43-62.

O’Kelly, M. J. (1952) St Gobnet’s House, Ballyvourney, Co. Cork. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 57, 18-40.

Richardson, J. 1727. The great folly, superstition, and idolatry, of pilgrimages in Ireland; especially of that to St. Patrick’s purgatory. Together with an account of the loss that the publick sustaineth thereby; truly and impartially represented. Dublin: Printed J. Hyde

http://www.dioceseofkerry.ie/page/heritage/saints/st_gobnait/ (accessed 21/01/2013).

http://www.seandalaiocht.com/1/post/2010/11/st-gobnets-house-ballyvourney-co-cork.html (accessed 18/02/2012).