Being Christmas week this post has a Christmas theme and provides a brief overview of the relics of the nativity venerated by medieval pilgrims.

The Holy Land

The Holy Land was the ultimate destination for medieval pilgrims, it was here that Jesus Christ was born, lived, died and was resurrected. So you could say, the pilgrims who came here were spoilt for choice, having access to wide range of sites associated with the New and Old Testament and the life of Christ.

Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus, was a must see for medieval pilgrims and many would have timed there visit to coincide with Christmas.

Pilgrims coming to Bethlehem at Christmas time (circa 1875) by photographer Félix Bonfils (Library of Congress)

Within the town of Bethlehem, the traditional site of the birth of Christ was marked by the Church of the Nativity.

Interior of the Church of the Nativity 1930’s (Library of Congress)

The church was built over a cave that was believed to be the manger where Christ was born.

Grotto of the Nativity in the cave under the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem. Image taken ca. 1890 and ca. 1900 (Library of Congress)

Pilgrims were flocking to Bethlehem from the 2nd century AD. The Church of the Nativity was commissioned in 327 AD by the Emperor Constantine and his mother St Helena. This first church was not completed until 339 AD and it was later destroyed during the Samaritan revolts in the 6th century. The current church was built on top of the aforementioned one in 565 AD by the Emperor Justinian. This link will take you to a 3D virtual tour to the current Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

Today the church is a UNESCO Heritage Site.

Since early medieval times the Church has been increasingly incorporated into a complex of other ecclesiastical buildings, mainly monastic. As a result, today it is embedded in an extraordinary architectural ensemble, overseen by members of the Greek Orthodox Church, the Custody of the Holy Land and the Armenian Church, under the provisions of the Status Quo of the Holy Places established by the Treaty of Berlin (1878). (UNESCO Website)

In modern times Christmas services for Roman Catholics and Protestants are celebrated on Christmas eve and Christmas day, the 25th of December. The orthodox Churches ( Coptic, Greek, etc) celebrate on the 6th of January and the Armenian Orthodox on the 19th of January.

One of the early pilgrims to Bethlehem was St Jerome who visited here while on a pilgrimage around the Holy Land, before taking up permanent residence in 386 AD. While living in Bethlehem he set up a monastery and pilgrim hostel to help provide hospitality to the pilgrims who were visiting here.

Bethlehem was a small quiet place and was described circa 1231 AD as having only one street. This must have provided pilgrims with a nice change from the hustle and bustle of Jerusalem. The pilgrims who travelled here often came on donkeys as did the English pilgrim Margery Kempe in 1413 AD ( Chareyron 2005, 102). In the late medieval period pilgrims entered the church in a processional order signing hymns and carrying a lighted candle (ibid). The pilgrim Jean Thenaud arrived here bearing gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh and was greeted outside the shrine by candle-sellers . He describes his visit as follows

Pilgrims entered “a small room with a vault of fine marble and mosaic”. There beneath the rock, was the place where the Lord was laid, the crib for the ox and the ass, and the rock itself the place for the nails that held the rings for tethering the animals and the hole through which the star that guided the Magi was said to have disappeared and the place where they worshipped Him (Chareyron 2005, 103).

Irish evidence for pilgrimage to Bethlehem

Time does not allow for a full discussion of Irish pilgrimage to the Holy Land and I do intend to come back to the topic in another post. So very briefly it is hard to gage how many Irish pilgrims visited the Holy Land. The Irish annals record 6 pilgrimages to Jerusalem between the years 1060 to 1231 AD and the Chartularies of St Mary’s Abbey in Dublin record the pilgrimage of Richard and Helen de Trum (Trim in Co Meath) in the year 1230 AD. The most detailed account of an Irish pilgrimage to the Holy Land is that of the Irish Friar Symon Semeonis who set forth from Clonmel in 1323 AD with his companion Hugh the Illuminator and who on his return he complied an account of his travels. These records represent only a fraction of Irish pilgrimages to the Holy Land and tell us little about how the Irish pilgrims experienced the Holy Land.

Nativity Relics in Europe

Pilgrims did not have to travel as far as the Holy Land to venerate the birth of Christ, as relics of the nativity, ranging from hay from the manger to the shift the Blessed Virgin gave birth in, were to be found at shrines across European. The following is a snapshot of some of these relics.

The Relics of the Magi at Cologne

The cathedral church of Cologne in Germany held the relics of the Three Magi and was a major centre of pilgrimage in the late medieval period. Located on a number of important trade route including the River Rhine the city attracted vast numbers of pilgrims each year.

According to the Gospel of Mathew the ‘Magi’ were three Kings from the east who journeyed to Bethlehem following as star to pay homage to the ‘one who has been born king of the Jews’. The Magi were also the first Christian pilgrims.

So how did the Three Magi end up in Germany? According to legend the corporeal relics of the Magi were discovered by St Helena (mentioned above), the relics were translated to the church of Saint Sophia at Constantinople and at a later date were brought to Milan. In 1160 AD following the sack of Milan, Frederick Barbarossa brought the relics from the Basilica de Sant’ Eustorigo to Cologne. Later an elaborate reliquary of gold silver and enamels and precious stone was constructed to hold the holy relics. The reliquary was commissioned by Philip von Heinarch Archbishop of Cologne (1167-1191) and made by Nicholas of Verdun. Pope Innocent IV granted a plenary indulgence to Cologne in 1394 AD which was an additional attraction for pilgrims to visit here.

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales tells that the wife of Bath had travelled thrice to Jerusalem and once to Cologne implying the shrine was well-known to English pilgrims.

Irish devotion to the Thee Magi is represented in Irish medieval sculpture for example the east face of Muiredach’s High Cross at Monisterboise, has a depiction of the Adoration of the Magi.

The Adoration of the Magi is also represented on the gable of Ardmore Cathedral church. Also one of the alters at the Franciscan Friary in Waterford city was dedicated to the Three Magi.

Three Magi at Ardmore Cathedral

The fifteenth century tomb at Strade abbey in Co Mayo depicts the Three Magi, St Thomas á Beckett, SS Peter and Paul and the figure of pilgrim kneeling. It is very likely that the iconography of the tomb indicates the deceased had been on pilgrimage to Cologne, Canterbury and Rome.

Tomb depicting the three magi at Strade Abbey (image taken http://hdl.handle.net/2262/39072)

Relics of the Nativity at Aachen

Approximately 61km from Cologne is the shrine of Aachen, another very popular European pilgrim shrine. Aachen had a miraculous image of the Virgin Mary along with a number of relics of the nativity. The relics included the nightgown worn by the Blessed Virgin, the swaddling clothes of the Christ Child, the loin cloth of Christ and a cloth that the decapitated head of St John the Baptist was laid on. It was also the burial-place of the Emperor Charlemagne who was canonised in 1165 AD and the cathedral also possessed the relics of St Ursula.

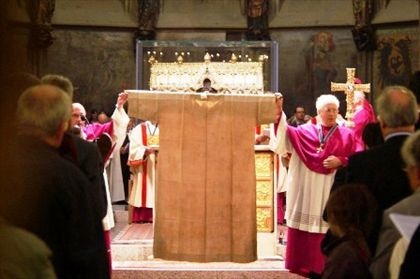

Marienschrein (1238)/The shrine of Mary, contains the relics , shift of the Blessed Virgin, the swaddling-clothes of the Infant Jesus, the loin-cloth worn by Christ on the Cross, and the cloth on which lay the head (image taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aachen_cathedral_007.JPG)

Many high status pilgrims travelled here and the Queen of Hungary came to Aachen in 1337 AD, with an escort of 700 knights.

Aachen became an immensely popular pilgrim site and attracted so many pilgrims it became tradition to display the relic every seven years for 15 days, between the 10-24th of July, on the Aachener Heiligtumsfahrt. This is a tradition which continues to present time. The first “Heiligtumsfahrt” (pilgrimage) took place in 1349 and 2014 will be the date for the next. To give you some idea of the shrines popularity, in 1496 AD the gatekeepers counted 147000 pilgrims entering Aachen during the 15 days the relics were on display. It was said the pilgrims left 85000 gulden at the shrine (Chunko 2009, 1-2). The shrine also offered a plenary indulgence to pilgrims.

The well known English pilgrim Margery Kempe made pilgrimage to here in 1433 AD when she travelled on pilgrimage from Danzig to Wilsnack and on to Aachen, where she saw the ‘virgin’s smock’.

The shrine also sold pilgrim badges depicting the relic of the Virgins nightgown/shift. These badge began to be made from the 1320s and some of these badges have turned up in archaeological excavations in London.

Chartres in France

The cathedral church at Chartres in France possessed the Sancta Camisa the shift worn by the Blessed Virgin when she gave birth to the Christ child. The relic was given to the church in 876 AD by Charles the Bald, who had brought it here from Constantinople. It was enclosed in a reliquary shrine called the Sainte-Chasse and many miracles are associated with this relic. Most pilgrims came here for the Marian feast of the Presentation, Annunciation and Assumption and the feast of the Nativity of the Virgin. As at Aachen pilgrim badges depicting the holy garment were sold to pilgrims in the later medieval period.

The relic of the Virgins nightgown at Chartres cathedral (image takenhttp://sites.tufts.edu/textilerelics/2011/02/08/marian-relics/)

Other Relics of the Christ Child

From the 11th and 12th century devotion to the Christ Child increased in Europe with SS Bernard of Clairvaux and Francis of Assisi actively promoting devotion to the Christ Child, and relics of the umbilical cord, foreskin, fingernails and milk teeth of Christ were to be found across Europe.

Rome with its vast collections of relics also had relics of the Nativity. The church of St Maria Maggiore possessed part of the crib in the form of boards from the manager. The board are believed to have supported the crib used by Christ and were brought here by Pope Theodore (640-649) from the Holy Land.

Another Nativity relic was found at the Archbascilica of St John Lateran where a section of the ‘Holy Umbilical Cord’ of Christ was kept. The last milk tooth of the Christ Child was housed at the abbey of Saint Médard at Soisson in France. Finally up to 8- 14 churches claimed to possess the Holy Prepuce/ Foreskin of Christ . These churches include Antwerp, Coulombs, Chartres, Charroux, Metz, Conques, Langres, Anvers, Fécamp, Puy-en-Velay, Auvergne, Hildesheim, Santiago de Compostela and Calcata.

Closer to home Christchurch Cathedral in Dublin had in its relic collection a fragment of the crib while Reading Abbey in England had another a relic of the umbilical cord and Our Lady’s Shrine at Walsingham, also in England attracted pilgrims to visit relics of Mary’s milk.

Conclusions

The birth of Christ was one of the most important feasts in the Christian calendar and each year it was celebrated by Christians with special liturgy and nativity plays. There was great devotion to the Christ Child and the Blessed Virgin in the Medieval world. Christmas time would have inspired some to take their devotion further by embarking on a pilgrimage to either the Holy Land or one of the many relics of the nativity which were scattered across Europe. As most people preferred not to travel in Wintertime most would have stayed at home for Christmas and planned their pilgrimages for Spring or Winter.

References

Bugslag, J. 2009. ‘Chartreuse de Champol’ In Encyclopaedia of Medieval Pilgrimage. Boston: Brill, 96-99.

Chareyron, N. 2005. Pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages.. Translated by W. Donald Wilson. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chunko, B. 2009. ‘Aachen’, Encyclopaedia of Medieval Pilgrimage. Boston: Brill, 1-2.

Donovan, S. 1908. Crib. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 22, 2013 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04488c.htm

Lins, J. 1907. Aachen. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 20, 2013 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01001a.htm

Lutz, G. 2009. ‘Cologne Cathedral’ In Encyclopaedia of Medieval Pilgrimage. Boston: Brill, 114-115

MacLehose, W. 2009. Relics of the Christ Child’ In Encyclopaedia of Medieval Pilgrimage. Boston: Brill, 601-603.

Mulcahy, E. 2012. ‘Symon Semonis The Franciscan Pilgrim.’ http://edelmulcahy.wordpress.com/2012/04/17/symon-semeonis-franciscan-pilgrim/

Aachen Cathedral . http://www.live-like-a-german.com/germany_related_articles/show/Aachen-Cathedral

Birthplace of Jesus: Church of the Nativity. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1433

Marian Relics 20011. http://sites.tufts.edu/textilerelics/2011/02/08/marian-relics/

http://www.medievalists.net/2013/12/09/the-holy-foreskin/

http://www.mariedenazareth.com/8137.0.html?&L=1

http://www.animatedmaps.div.ed.ac.uk/Divinity2/pilgrimages.html

he Aachen Cathedral is a major pilgrimage church and the burial place of Charlemagne and Holy Roman Emperor Otto III. The shrine to St. Mary holds the four great Aachen relics: St. Mary’s cloak, Christ’s swaddling clothes, St. John the Baptist’s beheading cloth and Christ’s loincloth. Following a custom begun in 1349, every seven years the relics are taken out of the shrine and put on display during the Great Aachen Pilgrimage. This pilgrimage most recently took place during June 2007. – See more at:

http://www.live-like-a-german.com/germany_related_articles/show/Aachen-Cathedral#sthash.PcI6PX27.dpufhe Aachen Cathedral is a major pilgrimage church and the burial place of Charlemagne and Holy Roman Emperor Otto III. The shrine to St. Mary holds the four great Aachen relics: St. Mary’s cloak, Christ’s swaddling clothes, St. John the Baptist’s beheading cloth and Christ’s loincloth. Following a custom begun in 1349, every seven years the relics are taken out of the shrine and put on display during the Great Aachen Pilgrimage. This pilgrimage most recently took place during June 2007. – See more at:

http://www.live-like-a-german.com/germany_related_articles/show/Aachen-Cathedral#sthash.PcI6PX27.dpuf

![Worcester Cathedral. ( By Merlincooper at en.wikipedia Later versions were uploaded by Newton2 at en.wikipedia. [CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5) or CC-BY-SA-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://pilgrimagemedievalireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/images.jpg?w=640)