I’m delighted to introduce a new guest post by Dermot Mulligan, Museum Curator, Carlow County Museum on St Willibrord. The Feast of St. Willibrord, Patron Saint of Luxembourg, will be celebrated with an ecumenical service in the Cathedral of the Assumption, Carlow Town at 7.30pm on Tuesday November 7t. In June of this year a ‘Relic of St Willibrord’ now on displayed in the Cathedral was presented by the people of Luxembourg to Carlow to say ‘thank you’ for training and ordaining him in the 7th century. Dermot’s post explains Willibrords ‘connections with Carlow, how and why his relics is now in Carlow. He also tells us about Carlow Museum’s new yearlong exhibition on St. Willibrord, his time in Carlow, his mission etc.

Re-discovering St. Willibrord, Patron Saint of Luxembourg and his County Carlow Connection by Dermot Mulligan, Museum Curator, Carlow County Museum

On Monday June 5th,, 2017 in the Basilica of St. Willibrord, Echternach, Luxembourg the Most Reverend Jean-Claude Hollerich, Archbishop of Luxembourg presented a specially commissioned ‘Relic of St. Willibrord’, Patron Saint of Luxembourg, to the Most Reverend Denis Nulty, Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin. St. Willibrord is one of the most important Saints in Europe spending twelve years in county Carlow before he led a mission to the continent in AD 6901. The Relic is a gift from the people of the town of Echternach, Luxembourg to honour the near 1,330-year link between both areas and to say, ‘thank you’ to county Carlow for training and ordaining Willibrord in the 7th century.

St. Willibrord as featured in a stain glass window in the Basilica of Echternach, Luxembourg. Photo Carlow County Museum.

Both Bishop Nulty and the Right Reverend Michael Burrows, Bishop of Cashel, Waterford, Lismore, Ferns, Ossory and Leighlin led a joint ecumenical diocesan pilgrimage of nearly sixty people from Carlow to Echternach not only to accept the relic but to also partake in the UNESCO World Heritage Status annual ‘hopping procession’ in honour of St. Willibrord in Echternach. The Carlow pilgrims are the first known Irish group to partake in this centuries old procession2. The procession is the culmination of three days’ celebrations that begin on Pentecost/ Whitsun Sunday every year in honour of St. Willibrord.

The first known written reference to the hopping procession in Echternach appears in a collection of legal texts dated AD 1497. This reference gives the impression that this particular custom originated much earlier. The exact origins of the hopping procession are unknown. The saga of Veit the Tall, an Echternach fiddler, suggests that the custom originated around the time of St. Willibrord. The hopping custom almost certainly arose in connection with the tithe processions which occurred directly after Pentecost Sunday when people from all the parishes under the abbey’s authority were required to walk to Echternach in a procession. However, there are those who say that it is a vestige of a pagan ritual which has been absorbed into the Christian tradition3.

Hopping Procession in honour of St. Willibrord, over nine thousand people hop a two kilometer route from the monastery to the Basilica and past St. Willibrord’s tomb. Photo Carlow County Museum.

The Relic is a piece of his bone, and is contained within the rose window of a scale model of the Basilica of St. Willibrord, which a bronze statue of a young missionary St. Willibrord is holding in his right hand. He holds his crozier in his left hand. Willibrord is standing on a piece of sandstone taken from the remains of his original abbey, which is in the crypt of the Basilica. The Echternach based Willibrordus Bauverein (Willibrord Foundation) commissioned German artist Mr. Bernd Cassau to make the beautiful statue.

The Relic is a piece of his bone, and is contained within the rose window of a scale model of the Basilica of St. Willibrord, which a bronze statue of a young missionary St. Willibrord is holding in his right hand. He holds his crozier in his left hand. Willibrord is standing on a piece of sandstone taken from the remains of his original abbey, which is in the crypt of the Basilica

The Relic is a piece of his bone, and is contained within the rose window of a scale model of the Basilica of St. Willibrord, which a bronze statue of a young missionary St. Willibrord is holding in his right hand. He holds his crozier in his left hand. Willibrord is standing on a piece of sandstone taken from the remains of his original abbey, which is in the crypt of the Basilica

Through the mists of time his Carlow connection, for the most part, had been forgotten. Pierre Kauthen, former President of the Willibrordus Bauverein, speaking in Carlow, stated “our historians long thought that Willibrord’s monastery was situated at Mellifont or Clonmacnoise. It was your historian, Prof. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín who located it on the site of Killogan/ Clonmelsh, Co Carlow” 4. Professor Ó Cróinín, based in the Department of History, NUI Galway, first wrote about Willibrord in 1982 and has published many papers on Rath Melsigi, Willibrord and his contemporaries since then5 + 6.

Over the course of the following thirty-five years this historical connection between both areas has been re-established. During April 2000, the Willibrordus Bauverein visited Carlow for the first time7. In 2002 His Excellency, Henri, the Grand Duke of Luxembourg, paid a state to Ireland, and in 2009, Her Excellency, Mary McAleese, President of Ireland, as part of her state visit to Luxembourg, visited Echternach.

St Willibrord is the Patron Saint of Luxembourg and is buried in the Basilica of Echternach, which is the centre of his monastic foundation. Located near Milford, Co Carlow, is the archaeological site Rath Melsigi8. During the seventh and eighth centuries, this site was the most important Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical settlement in Ireland9. It was here from AD 678 to c. AD 720 that Willibrord and many other Englishmen were trained for the continental mission. In AD 690 Willibrord led a successful mission from Carlow, made up of Irishmen and Englishmen. As part of his abbey in Echternach, he established a very important scriptorium and for a considerable period the abbey produced many of the bibles, psalms and prayer books that are to be found today in the great libraries of Europe. It is likely that the first generation of these scribes were from Co. Carlow or had trained here. Many of the earliest Anglo-Saxon manuscripts were written in Irish script by Irish monks based either in Britain or by Anglo-Saxons who were trained by the Irish.10

From Echternach Willibrord continued to co-ordinate missions to the surrounding countries until AD 739, when he died aged 81. He is buried in Echternach, and he is said to be the only saint buried in Luxembourg. St. Willibrord’s signature is the oldest datable signature of an English person and oldest datable use of Anno Domini (A.D.) dating. Both are contained in a book most likely written in Co. Carlow in advance of his mission. Today the book is known as the ‘Calendar of Willibrord’ and is housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. The Calendar is a listing of saints’ feast days that were being honoured during Willibrord’s lifetime11.

Willibrord is relatively unknown in Ireland, but much devotion and religious festivals are held to this day in his honour in the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg. The most famous is the annual hopping procession, a dance that dates back to, if not predates St. Willibrord’s lifetime. The hopping procession takes place annually on the Tuesday after Pentecost Sunday and sees thousands of people descending on Echternach to partake along with dozens of Cardinals, Archbishops and Bishops from across Luxembourg, Belgium, Holland and Germany.

On Tuesday, June 6th, after 8am Mass, the assembled clergy lead the Relic of St. Willibrord out from the Basilica of St. Willibrord into the adjoining square of the secondary school where thousands have gathered. The procession is led by a large group singing the ‘Litany of St. Willibrord’ who are then followed by local firemen carrying the Relic along the approximately 1.5km route. They in turn are followed by between 10,000 and 13,000 people hopping from their left to right foot in his honour. Participants wear white shirts/ blouses with black trousers/ skirts and hop in rows of five joined together by holding white handkerchiefs. Each of the thirty-nine hopping groups participating in the 2017 procession were led by a marching band all playing the exact same tune. The procession is a physical pilgrimage, and those who participate are known as the ‘people who pray with their feet’12.

The Carlow hopping pilgrims were wonderfully led by members of the Presentation School Band from Carlow town under the baton of Edwina Hayden, Music Teacher. The Carlow pilgrims, group number 29 of 39, received a warm welcome from the many thousands who lined the streets to watch the procession. The group was joined by several people, also hopping for the first time, who had heard of an open invitation to join with the Carlow pilgrims. The group hopped through the medieval streets of Echternach before entering the Basilica, hopping down the side aisle, down into the crypt located under the altar and past St. Willibrord’s remains.

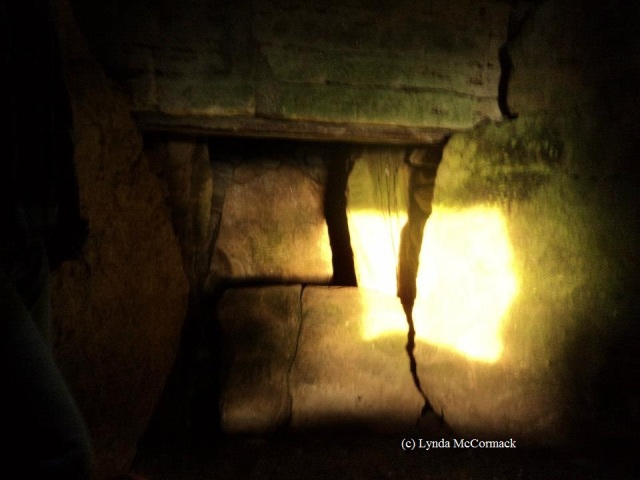

Arriving on Thursday 22nd June, twenty-nine visitors travelled from Echternach to Carlow and spent four days here. The highlight was the ‘Walk with Willibrord’ which took place on Saturday June 24th. The Relic was walked over 13km from St Laserian’s Cathedral, Old Leighlin to the Cathedral of the Assumption, Carlow via the beautiful Barrow Way, a National Waymarked Trail, along the banks of the river Barrow. The walk was make up of nearly two hundred people from Ireland and Luxembourg and led by Bishops Burrows and Nulty. Earlier that same morning the visitors from Echternach had a special visit to Rath Melsigi. As a group, with a number of Carlow chaperones and permission from the landowners, they held a short reflection and all joined hands in a circle around the 7th century cross hopping on the spot while humming the hopping tune.

Members of the Willibrordus Bauverein (Willibrord Foundation) visiting Rath Melsigi in advance of the ‘Walk with Willibrord’ on Saturday June 24th last. They are gathered around the granite cross which dates from the time when St. Willibrord and his colleagues were in the area undertaking their studies. Photo: Carlow County Museum.

The ‘Walk with Willibrord’ began at the Holy Well in Old Leighlin at 10am on the morning of Saturday 24th. The ‘Eucharist of the Saints’ service continued in the nearby St. Laserian’s Cathedral, Carlow’s oldest working building.

At the end of the service, shortly after 11am, the relic with music from three pipers from the Killeshin Pipe Band the two hundred people, led by Bishops Burrows and Nulty, began the walk to Carlow Cathedral.

A view of the ‘Walk with Willibrord’, entering the Barrow Way on the Banks of the River Barrow at Leighlinbridge. Photo: Sean McDonnell.

In Carlow town the Relic was walked in procession from St. Clare’s Church to St. Mary’s Church and then onto the Cathedral of the Assumption. Members of the Carlow Fire Service carried the Relic through the streets of the town, mirroring the tradition in Echternach where their Fire Service carry the Relic at the head of their annual hopping procession. The procession in Carlow was led by the Presentation Band who had led the Carlow pilgrims in Echternach. They played the hopping tune as they approached the Cathedral and the visitors from Echternach hopped to the front door of the Cathedral, the first known occasion that hopping in procession has been undertaken in county Carlow13. The Relic was blessed by Bishop Nulty with Holy Water taken from both Old Leighlin and Echternach holy wells.

Members of the Willibrordus Bauverein and people from Carlow hopped in procession for the last kilometer of the ‘Walk with Willibrord’ to Cathedral of the Assumption, Carlow town. Photo: Grzegorz Kaczorek.

Carlow County Museum, who coordinated the project from the Carlow side, has opened a free yearlong exhibition about St. Willibrord, his time in Carlow, his mission, his present-day impact and the UNESCO World Heritage Status ‘hopping procession’. A copy of Willibrord’s own hand writing, the oldest datable signature of an English person, is on display along with samples of the beautiful manuscripts that were produced in Echternach. It is clear that several of them are influenced by the Irish manuscripts that these islands are famous for. The method of making a manuscript is shown in detail, from producing the inks and the vellum to how the letters and designs were laid out.

View of the ‘St. Willibrord, Patron Saint of Luxembourg and his County Carlow Connection’ exhibition in Carlow County Museum. Photo: Carlow County Museum.

The project has been shortlisted in the Chambers Ireland ‘Excellence in Local Government Awards 2017’.

References:

- ‘Calendar of Willibrord’, MS. Lat. 10837, fol. 39v, Bibliothèque National de France, Paris. Translation from Latin to English provided by Professor Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Department of History, NUI Galway.

- According to the Willibrordus Bauverein, who organise the procession, they have no records of any Irish groups participating. The first known Irish participaticants in the hopping procession was in 2010 and the second known was in 2015. Although, a few Irish people have participated in the past but their participation would not have been officially recorded.

- Emile Seiler, ‘The Echternach Hopping Procession’, Carloviana, 2000 edition, p. 55

- Speech by Pierre Kauthen, former President of the Willibrordus Bauverein (Willibrord Foundation) on Friday June 23rd, 2017 at 8.30pm at the Carlow County Council reception in the Seven Oaks Hotel, Carlow for the Willibrordus Bauverein.

- Prof. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Department of History, NUI Galway, ‘Pride and Prejudice’, Peritia Vol.1 (1982) pp. 352-62.

- Prof. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Department of History, NUI Galway, ‘Rath Melsigi, Willibrord and the Earliest Echternach Manuscripts’, Peritia, Vol. 3 (1984) pp. 17-49.See also footnote 30 which in abbreviation states “Mr Kenneth Nicholls of University College, Cork, has proposed that the site which occurs in some early charters as Cluain Melsige (now Clonmelsh, Co. Carlow) is identical with the Rath Melsigi of Bede’s account. The identification of Cluain Melsige with Rath Melsigi had been made independently by the late Éamon de hÓir, Irish place names Commission … Fr Columcille Conway had suggested the same identification (see Aubrey Gwynn and R.N Hadcock, Medieval religious houses: Ireland (London 1970) 402”.

- Emile Seiler, ‘St. Willibrord’, Carloviana, 2000 edition, p. 55

- Record of Monuments and Places, CW012-025 Garryhundon.

- Professor Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Department of History, NUI Galway.

- Prof. Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Department of History, NUI Galway, ‘Rath Melsigi, Willibrord and the Earliest Echternach Manuscripts’, Peritia, Vol. 3 (1984) pp. 17-49.

- Calendar of Willibrord’, MS. Lat. 10837, fol. 39v, Bibliothèque National de France, Paris.

- Emile Seiler, ‘The Echternach Hopping Procession’, Carloviana, 2000 edition, p. 55

- There are three known occasions when hopping has taken place in county Carlow. In April 2000 and June 2017, the Willibrordus Bauverein, along with their Irish chaperones, hopped in a circle around the 7th century cross at Rath Melsigi. The conclusion of the ‘Walk with Willibrord’ in Carlow town, June 24th, 2017, is the first known hopping procession in county Carlow in the manner that takes places in Echternach, ie, people in rows of five, holding handkerchiefs and with a marching band playing the hopping tune.

Save