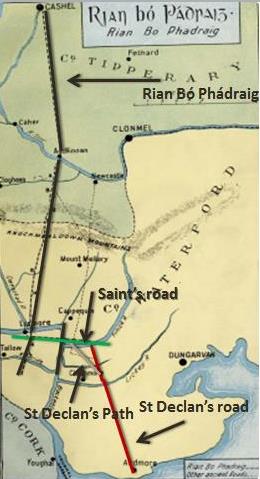

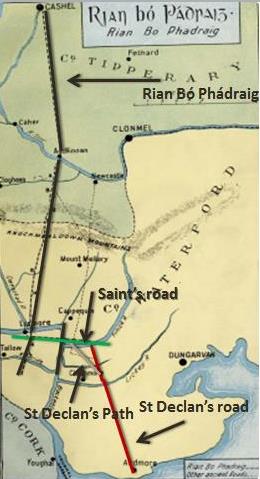

St Patrick and his cow are the focus of part three of my series of post on the saints and their animals. Like SS Ciarán of Clonmacnosie and Manchan of Lemanaghan, St Patrick is also associated with a cow. Unlike the previous two cows, Patrick’s cow could not produce an endless supply of milk however she did have some magical abilities namely the strength to plough a deep trench across two counties. The route of the trenches made by the cow’s horns are said to have created the ancient road known as the “Rian Bó Phádraig” or “Track of St Patrick’s Cow”. Aspects of the route of this road are now incorporated into the modern walking route St Declan’s Way. The road itself is a complex topic and I will discuss this in full at a later date. Briefly the road is said to have run from Cashel through Ardfinnan, crossing the River Tar near Goatenbridge, heading south over the Knockmealdown Mountains in to Co Waterford, passing close to eastern side of the town of Lismore, crossing the River Blackwater and Bride before terminating in the townland of Fountain in the parish of Kilwatermoy.

Map showing the Rian Bó Phadraig & St Declan’s road

In the course of my research I came across second road also associated with Patrick and his cow, known by the same name but located in Co Limerick. This post will just focus on the creation myth of the two roads. I will explore the route of both roads another time.

Legend of the St Patrick’s Cow and the Creation of the Rian Bó Phádraig in Tipperary & Waterford.

The earliest written account of the story of St Patrick’s cow and the Rian Bó Phádraig dates to the 18th century when it was recorded by antiquarian Charles Smith in 1746.

Smith recounted that local people referred to a double trench in Co Waterford that they called the Rian Bó Phádraig, he believed that the trenches were the remains of an ancient highway linking Cashel to Ardmore. In 1746 the trench was clearly visible in the Barony of Coshmore and Coshbride, Co Waterford. Smith also says that the ‘…country people affirm that it might be traced from its entrance into this County[Waterford] as far as Cashel into the County of Tipperary‘.

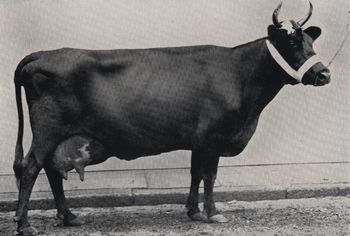

Traditional Irish breed of cow called the moiled cow, with her calf.

According to Smith

They [Irish peasants] affirm, that when St Patrick was at Cashel, a cow belonging to that saint had her calf were stolen and carried off towards Ardmore, which she pursued, and with her horns made this double trench the whole way; others say it was the cow was stolen , and that she returned home of herself and in the same manner plowed up the ground with her horns… (Smith 1746, 355).

In 1877 Richard Brash provided an account of the tradition from the Ardmore area . In this account we are told the saints cow was white and her calf was stolen from Cashel by people from Ardmore.

It is fabled that St Patrick when living at Cashel had a favorite white cow, whose calf was stolen and carried off to Ardmore; the animal, furious at its loss, followed the robbers, tearing up the ground with its horns as it rushed along, and forming two trenches which can be traced in many places to the present day. This track is name by the peasantry, Rian-bo-Phadrig, that is, the track of Patrick’s cow.

Brash also makes reference to some other variations of the legend which stated that

…the cow was stolen from Cashel and brought to Ardmore, from, whence it made its escape, and facing homewards, tore up the tracks….

20th Century Folklore of the Rian Bó Phádraig in Tipperary

Power in his 1905 article called ‘The “Rian Bó A Phádruig” (The Ancient Highway of the Decies)‘ recounts a synopsis of folklore for the road that was at this time ‘told from Ardfinnan to Ardmore’.

St. Patrick’s cow, accompanied by her calf, was grazing peacefully on the alluvial flats by the side of the Tar river, in the extreme south of Tipperary, when the calf was abducted by a wily cattle-thief from Kilwatermoy, or somewhere to the south of the Bride, in the County Waterford. The robber, with his booty, started in haste for his home, eighteen or twenty miles distant, and shortly afterwards the cow, having discovered her loss, commenced a distracted pursuit. In her fury, as she went, she tore up the earth with her horns….till she overtook the robber, to whom she promptly gave his deserts (Power 1905, 121).

A Kerry cow another traditional Irish breed of cow.

During Power’s fieldwork on this ancient road (Rian Bó Phádraig) it was discovered that in the area around Lismore some of the fields where the route of the road passed through were called by names such as páirc a’ Rian the field of the Rian.

The spot where the cow took her revenge was said to be on the south side of the Bride, and adjacent to the Camphire Tallow road, in the modern townland of Fountain. The spot was said to be in a field known as Clais a’ Laoigh or ‘the trench of the calf’, in which a depression was pointed out as the spot where the cow took her revenge. This spot was marked on the 1927 ed. of the OS 6-inch map but not earlier maps of the area and may noted in 1927 as a result of Power’s article published some years earlier.

The field known as Clais a’ Laoigh the trench of the calf at Fountain Co Waterford

Over the last 100 years or so the field has been intensively cultivated and no physical traces above ground are visible.

20th Century Folklore of the Rian Bó Phádraig from Waterford

Early 20th century folklore from Kilwatermoy and Cappoquin in Co Waterford provides further variation of the tale, with St Patrick having a greater involvement in the story but it is still the cow who is the main actor of the tale. Interestingly cow was said to have been carried off by people from outside the parish of Kilwatermoy.

The Schools Manuscripts Essays for Kilwatermoy (roll no. 5385, 322 ) records that when Patrick and his cow were visiting the parish his cow was stolen.

An incident in connection with Saint Patrick’s visit to the parish. The story is told by the oldest people that when Saint Patrick visited this parish he took with him a cow and calf. When he had been some time there, it is said that the calf was stolen by some of the neighboring people. Afterwards they buried the calf in a field near Sapperton.

The cow then searched everywhere for the calf and finally scented it to the field where it was buried. She then in a great, rage, and rooted up the ground furiously. There is still to be seen in this field a big hole, which shows the burial-place of the calf.

Sapperton townland is located on the eastern side of Fountain townland where Power’s research identified the field known as Clash na Laoigh. Power in 1905 noted the legend of the Rian was very much associated with the Kilwatermoy area and he goes on to say

So generally known was the legend, and so intimately did popular belief associate the robber with this district south of the Bride, that, half a century ago, natives of Kilwatermoy parish, when away from home, would not very willingly admit their birth-place (Power 1905, 121-122).

The Schools Manuscripts essays for the nearby town of Cappoquin ( roll no. 15457 page 125) recorded another version of the tale where St Patrick and his cow were visiting Cappoquin. Again the cow creates the road while in pursuit of her stolen calf.

Long ago when St Patrick was passing through Cappoquin he went by Mt River because in his time there was a ford across that way. He had a cow and this cow was after having a calf. The calf was stolen one night. The cow went along a path to find the robber and at last found him at the end of the bohereen and it is said that she knew it by instinct. That path is now called ” the Path of St Patrick’s Cow”.

1st ed. OS 6″ map depicting the Casán na Naomh at Mount Rivers

Mount Rivers is an estate on the east bank of the River Blackwater. Power recorded a ford here called Áth Mheadhon – the middle ford across the River Blackwater. The 1st ed OS 6″ maps record the route of a road called Cassaunnanaeve or Casán na Naomh – ‘the Saint’s path’. Power believed that this was an ancient road linking Lismore with Affane (Power 1905, 123). This road was part of a network of roads that included the Rian Bó Phádraig and St Declan’s road. I wonder had the distinction between the two roads blurred by the 1930’s.

Physical Traces of the Cow’s Journey

Like stories associated with St Manchan’s cows and St Ciarán’s cow St Patrick’s cow left a visible physical mark on the landscape.

In 1746 by Charles Smith described the route of the cow as ‘a large double trench’, in the mountainous parts of the Barony of Coshmore and Coshbride ” Co Waterford.

In 1905 Rev P Power carried out a detailed survey of the entire route of the Rian within the two counties of Tipperary and Waterford using local folklore and fieldwork he traced the Rian from Ardfinnan over the Knockmealdown mountains via Carraig a Bhuidéal pass, down across the Blackwater, over the River Bride to Kilwatermoy parish where it ended in the townland of Fountain, beside the Camphire –Tallow road. As mentioned above Power had found that in many of the townlands in Co Waterford where the road passed through field names reflected the route of the road. He was also able to located sections of intact physical remains as well as the location of sections of the road more recently destroyed.

Facing North towards Cashel from Beárna Cloch na Bhuidéil on the Waterford Tipperary County Boundary line

When I carried out fieldwork on the route of the Rian in 2000 the road was still traceable on the southern slopes of the Knockmealdowns where it was represented as a 3m wide sunken road, in the ensuing years this section of road has deteriorated.

The Rian Bó Phádraig in Co Limerick

Another road also called the Rian Bó Phádraig is to be found in the Co Limerick. The road is found beside the ecclesiastical site of Ardpatrick which according to local tradition was founded by St Patrick.

Although the road bears the same name as the Waterford/Tipperary road it has a different origin legend. The Limerick Diocese website makes note that the parish of Ardpatrick was previously called Ballingaddy, ‘Baile an Ghadaihe’ or the ‘Town of the Thief’. There is however no connection with the theft of the saint’s cow and the formation of this road. The Ardpatrick Rian was also created by the physical actions of the cow. It was said the ‘slug of St Patrick’s Cow’s Horn’, Leaba Rian Bó Phádraig and it was said the road and stones at the entrance to the hill of Ardpatrick were the remains of what was once a road that linked Armagh to Ardpatrick. It was also said the Abbot of Armagh used this road to travel to Ardpatrick to collect his dues (see http://www.limerickdioceseheritage.org/Ardpatrick/hyArdpatrick.htm).

I am only beginning researching the Limerick road and I hope to find out more in the coming months. Like the Waterford Rian the Limerick road was not recorded on the 1st ed OS 6″ map for Limerick. The National School Essays (1939) for Ardpatrick make brief reference to the site of the road located on the west of Ardpatrick running up the hill to church. The essays record little folklore associated with the road only that the saint came here along the road and the old people of the area knew the road by the name Rian Bó Phádraig.

The Rian Bó Phádraig running to Ardpatrick

The earliest reference to road I have come across so far dates to 1866

Another great curiosity was the “slug of the horn of St Patrick’s little cow”. This animal it was that supplied the saint with his daily milk; and the cow might be seen painted on many a signboard’ (Lenihan 1866 721)

Westropp noted that in 1877 local people said

The “Slug of St. Patrick’s Cow” made when the unruly beast ran away from Ardpatrick, was called by Irish speakers Rian bo Phadhruig…

The latter is perhaps the closest tale to the Waterford/Tipperary road. Westropp also made note of the similarities in appearance between this road and the Waterford one.

Conclusion

I will be continuing my research on both roads in the coming months and I am planning to walk the surviving sections of roads in the Spring. Although St Patrick doesn’t really feature too much in the folklore of either roads, I have a great fondness for the Waterford/Tipperary tale with the feisty cow in pursuit of her calf . In my minds eye I can see a small white cow frantically ploughing her way across the land of Tipperary and Waterford at great speed, in a cloud of dust spurred on by the bellows of her calf.

References

Brash, R. 1877. The ecclesiastical architecture of Ireland, to the close of the twelfth century : accompanied by interesting historical and antiquarian notices of numerous ancient remains of that period.Dublin : W. B. Kelly: [etc., etc.]

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, U.C.D The Schools’ Collection, Cappoquin Volume 0637.

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, U.C.D The Schools’ Collection, Kilwatermoy Volume 0637.

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE, U.C.D The Schools’ Collection, Ardpatrick Volume 0509.

Lenihan, M. 1866. Limerick; Its History and Antiquities, Ecclesiastical, Civil, and Military: From the Earliest Ages, with Copious Historical, Archaeological, Topographical, and Genealogical Notes. Dublin: Hodges Figgis.

PhD research undertaken by myself.

Power, Rev. P. 1905. ‘The “Rian Bó Phádruig” (The Ancient Highway of

the Decies)’, JRSAI Vol. VI. XV, Fifth series, 110-129.

Smith, C. 1746. The antient and present state of the county and city of Waterford. Dublin: A. Reilly.

Westropp, T. 1916/1917. ‘On Certain Typical Earthworks and Ring-Walls in the County Limerick. Part II. The Royal Forts in Coshlea (Continued)’ PRIA, 444-492, 4