The medieval parish church and graveyard at Tullaghmelan is one of my favorite places to visit in south Tipperary. The name Tullaghmelan means the hillock of Maolán. Tradition holds that Maolán was a saint who had founded a church here in the early medieval period.

There is no visible early medieval features sat the site although a pronounced curve in the road that borders the graveyard may perhaps preserve an earlier enclosure.

The church is listed in a dispute between the Archbishop of Cashel and the Bishop of Lismore in 1260. In 1302-1306 it is recorded in the ecclesiastical taxation records of the diocese of Lismore (CPL; CDI).

At first glance Tullaghmelan is a typical medieval parish church a with rectangular plan, surrounded by a historic graveyard.

This lovely place is anything but ordinary. The graveyard is filled with some extraordinary eighteenth and early nineteenth century gravestones.

The east gable has largely collapsed and a number of mature trees are growing out of the wall. The west gable is still standing and still retains a central ogee-headed window, now in very poor condition. I’m not sure how much longer the window will survive as the surrounding wall is very damaged.

The church fabric is built of roughly coursed limestone and sandstone rubble (Farrelly 2014). It is hard to examine the fabric of the church as it is covered with think ivy. The church is entered by two opposing doorways in the north and south walls. Opposing doorways are also found at the nearby medieval parish church at Newcastle and are a common feature in medieval churches.

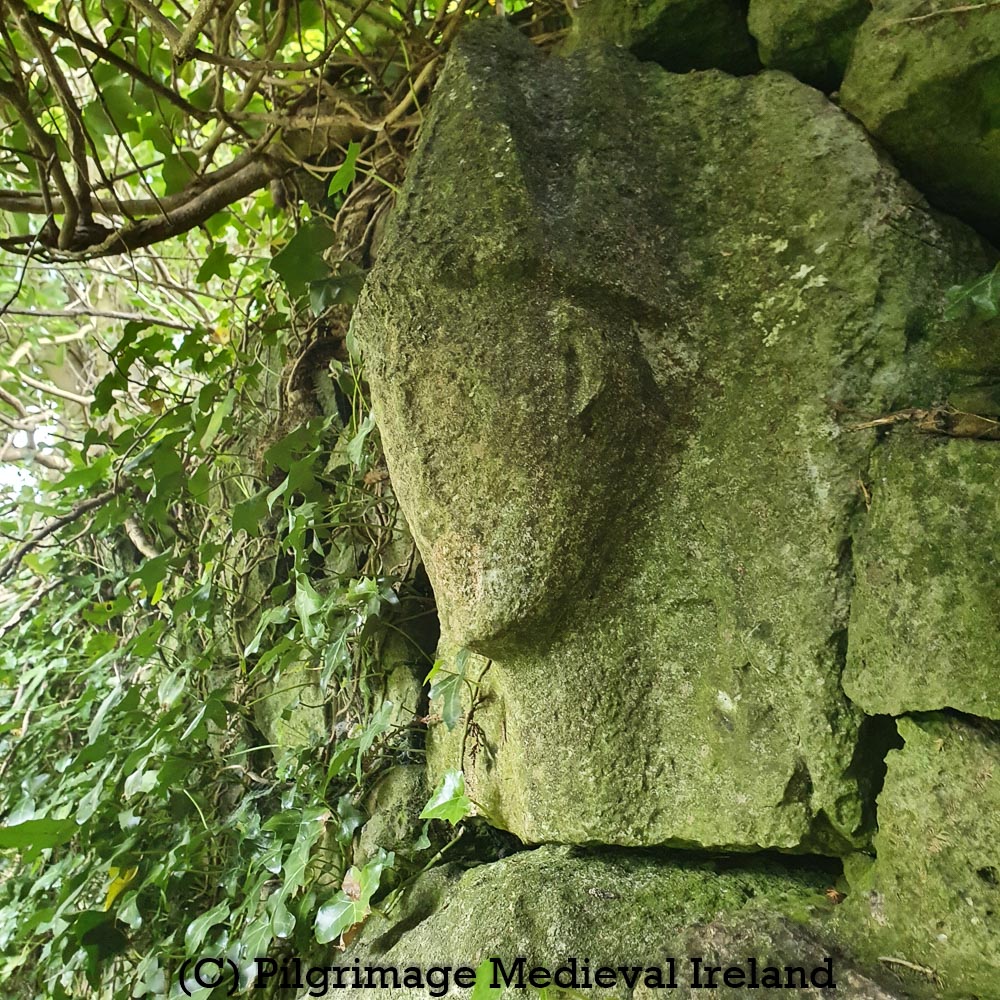

Unfortunately much of the northern doorway had collapsed but the lower section of the door still preserves carved stones hidden under the ivy.

The door in the southern wall is in a much better state of preservation. The doorway is finely carved pointed doorway, with hood-moulding. Hood-moulding dates to between the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries and is a common architectural feature of later medieval buildings.

Sitting above the doorway is a carving of a medieval bishop’s head.

The head is elongated with a pointed chin and small lug ears. It is held up be a long narrow neck. On top of the head is a type of head dress/hat worn by a bishop called a mitre.

The bishops face is badly weathered. It is still possible to see the almond-shaped eyes of the face. In the right light you can still just about make out the nose and mouth. The mitre has a conical in shape, with three vertical ridges running to the point at the top. There is a thick band with a herring-bone pattern, running around the base of the hat.

The head was recorded by Gary Dempsey of Digital Heritage Age. Gary produced a in a 3D photogrammetery model which can be view on sketchfab with the Tipperary3D page.

Portrait heads like the Tullaghmealan bishop are found at other ecclesiastical sites in Ireland. The parish church of St. Molleran in Carrick-on-Suir was built in the nineteenth century on the site of a Franciscan Friary. The building, incorporates the tower, part of the north wall and west doorway of the original friary church. The west gable retains fourteenth century pointed doorway. The head of a bishop wearing a conical mitre is carved in the column on the north side of the door.

Two carved heads of bishop’s heads are found in at medieval ecclesiastical site at Kilfenora Co Clare. One of the heads, a stern looking figure, sits above a pointed door way in the west end of the southern wall of what was the nave of the cathedral church. The door leads into a porch where there are three effigial tombstones also depicting bishops and clerics.

The second carved head is found in the north wall of the cathedral chancel. The head sits above a sedilia with a very elaborate tracery design.

Another medieval carved head of a bishop is found at the cathedral church of Kilmacduagh, Co Galway. The carving is very similar to the head over the sedila at Kilfenora, perhaps the two stones were carved by the same mason. The Kilmacduagh head sits over a finely carved pointed doorway in the south wall of nave of the cathedral church.

A large effigy of a bishop is found in the wall of the presbytery in the church at Corcomroe Cistercian monastery, Co Clare. The figure is built in the wall above the tomb of Conor na Siudaine O’Brien, King of Munster (d. 1267).

At Ennis Friary, Co Clare, a finely carved head of bishop forms a corbel/supports of the central tower in the church. According to the Monastic Ireland website

Images of bishops, abbots and archbishops in this location are often intended to depict the prelate who presided over building works. The presence of flanking angels suggests that the individual in question was deceased at the time of carving.

http://monastic.ie/tour/ennis-ofm-friary/#4

A carved head of a bishop also graces one of the corbels on the wall of the church at Holycross Abbey in Co Tipperary.

Its very interesting that all of the examples of portrait carvings of bishops listed above are found at monastic and cathedral churches. Tullaghmealan was not a particularly wealthy parish church. Perhaps it enjoyed a wealthy patron at the time the carved stone and doorway were made.

The Tullaghmelan bishop was drawing by George Du Noyer in the 1800s. He wrote the following about the stone

This drawing is offered as a characteristic example of the doorways of most of our old churches, which are so plentifully scattered over the eastern and south-eastern portions of Ireland. It is taken from the old church of Tullaghmelan, near Knocklofty, Co. Tipperary; the arch is of the depressed pointed form, the drip-moulding very prominent and broad; the entire door-head consists of only six stones, viz., two for the principal arch, and four for the drip moulding surmounting it. At the apex of the arch is a somewhat rude representation of the head of a bishop, crowned with a mitre of an exceedingly old form, and which was most generally in use during the twelfth century. The mitre looks as if formed of an external framework of metal, the ribs of which stood prominently out, and within which was the cap or head covering. The helmets most commonly in use in England, as well as on the Continent, during the thirteenth century, as we find in Stoddart’s “Vetusta Monumenta,” and from the Painted Chamber at Westminster, were constructed on this principle; the framework is mostly coloured yellow, as if to re present brass or metal, the intervening spaces being red or purple, as if to indicate the inner cap, called by the Romans “cudo” or ” galerus,” of dyed leather, cloth, or felt. I should not be surprised if on research we found that many of the mitres of our medieval ecclesiastics were constructed on precisely this principle.

Du Noyer 1857, 312-313;

The carving is also mentioned in the Ordnance Survey Letters where it is noted that the head is ‘supposed to represent ‘Maolan, Eapscop. [Bishop] 25 Dec‘ (O’Flanagan 1930, vol.1, 26).

I am by no means an expert of medieval building or architecture but I find it odd that the Tullaghmelan bishop is carved onto a flat stone (the back of the stone is visible in the interior wall). I would have expected the stone should have more of a wedge shaped if designed to be as an architectural feature. This makes me wonder if it could be a recycled fragment of a sepulchral effigy. I am struct by the similarity between this carving and one of the graveslabs at St. Fachtna’s Cathedral, at Kilfenora. The top of the stone also looks broken. I wonder if the carving could be a recycled graveslab? I really think this bishop requires further study.

Bishops head at Tullaghmelan parish church

St. Fachtna’s Cathedral, Kilfenora, County Clare – Tomb Effigy (http://hdl.handle.net/2262/11728)

Unfortunately the church building and the door have deteriorated structurally since my last visit and I worry that without some sort of intervention, the door and other parts of the church will collapse in the coming years. At the moment the ivy is holding the structure together. Sadly this is a common problem for medieval building across the country. I hate the thought of the bishop over the door not being there greet visitors to the graveyard into the future.

References

Du Noyer, George V. “Description of Drawings of Irish Antiquities Presented by Him (Continued).” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1836-1869), vol. 7, 1857, pp. 302–316. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20489878. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Hunt, J. 1974 Irish medieval figure sculpture 1200-1600, 2 vols. Dublin. Irish University Press.

Nugent, L. ‘A note on medieval figure sculpture at the medieval parish church of Tullaghmelan, Co Tipperary’ Decies 68, 17-23.

O’ Flanagan, Rev. M. (Compiler) 1930. Letters containing information relative to the antiquities of the county of Tipperary collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1840. Bray.

http://www.tara.tcd.ie/handle/2262/11728?show=full

Home