The 17th and 18th centuries in Ireland were a very interesting time in the history of Irish pilgrimage. Society experienced many changes, the Catholic religion practised by the majority became second to Protestantism the new religion of the state. It was a violent time of political upheaval and social change in which various conflicts culminating with the Cromwellian conquest of 1649-53, and the later Williamite Wars of 1689-91, resulted in a major shift in the social structure of Irish society, with the Irish catholic aristocracy being largely replaced by a new English protestant ruling class. Additionally churches and monasteries were dissolved, as were the monastic orders who controlled them, continuing the work of the reformation initiated by Henry VIII in the 16th century. State laws were imposed to curtail the religious freedoms of those who did not follow the state religion. Monasteries and churches were stripped of their valuables and many of the precious relics of the medieval period such as the Bachall Íosa or the miraculous statue of Our Lady of Trim were destroyed by iconoclasts. During the medieval period the majority of pilgrim sites were controlled by religious orders but following the dissolution the church often had little input into how the sites were accessed. Pilgrimage in a sense now came to be controlled of the pilgrims. Pilgrim rituals adapted and changed to these new circumstances, becoming more fluid and less formal. Despite the efforts of the State to suppress pilgrimage, the practice continued and in some cases thrived at a local and regional level.

One of the more interesting stories of pilgrimage from this period is found in the papers relating to the Power Shee family in the National Library of Ireland. Within these records are the papers of Mary Kennedy (1733-1784) whose maiden name was Shee. Mary transcribed a list of family births and deaths from her father William Shee’s prayer-book. The original list was written by William Shee (1694-1758) and his father, James Shee (1660- 1724) of Derryhinch/Derrynahinch Co Kilkenny.

Mary’s grandfather James was born in Derryhinch/Derrynahinch in 1660 to William Shee and Ellen Rothe. Both William and Ellen were descendants of prominent Kilkenny Merchant families. James began a tradition later continued by his son William of recording important life events in his prayer book. The list began with the date of James marriage to Mary Trapps (1660-1706) on the 25th of May 1684 (Ainsworth & MacLysaght 1958, 250). He subsequently recorded the birth of their children. Their first child William was born Friday the 8th of May 1685 but died sometime later. A second son George was born on the 11th of April 1686, the following year a daughter called Ellen was born ‘…Saturday the last of December 1687 between 7 and 8 in the morning.’ Elizabeth was born in June 1690 and a son Henry on the 13th November 1691. Another son who was also called William was born in 1693. In the prayer-book James writes the child was taken very ill on the 20th of March 1693 and wrote ‘I promised to make him a Church man if I found he had vovation’ but the boy died on the 8th of May the following year. Shortly after the child’s death another boy child was born in 1694 and he was christened William (Ainsworth & MacLysaght 1958, 250-251).

Some time in 1693/94 he writes

My daughter Ellen being very ill, I promised to make a pilgrimage to Our Lady’s Island, in honour of Our blessed Lady. This performed’ (Ainsworth & MacLysaght 1958, 250

Having lost two children James and his wife must have been very frightened for Ellen. We do not know what sickness the child had but the mortality rate for children was very high in 17th century Ireland. James and his wife are likely to have been able to afford medical care but as there had been few medical advancements since medieval times medical intervention had limited success. The death of children from what are today preventable and curable illnesses was a harsh reality for parents rich and poor.The decision for James to undertake a pilgrimage and to turn to the Our Lady for help is very understandable in the context of the time. Throughout the medieval period and up to early modern times there was a very strong belief that many diseases were caused by divine intervention. There was also a very strong belief in the power of the saints to heal and certain pilgrim sites were known for their healing powers. Even today there are holy wells around the county held to have the power to cure ailments related to certain parts of the body such as eyes, skin, and limbs etc. that still attract pilgrims in search of a cure. Vows of pilgrimage undertaken in times of crisis were common throughout the medieval and post medieval period. Additionally it was not uncommon a person to perform pilgrimage on behalf of a loved one who was too ill to travel.

James’s daughter Ellen was 6 or 7 years old when she fell ill and was too young and sick to undertake a pilgrimage on her own, so it was logical that her father would go on pilgrimage on her behalf. Lady’s Island was located in the southeast corner of Wexford in the barony of Forth and Bargy some 80km from Derryhinch. During the 17th century a unique dialect of old English called Yola was widely spoke by the inhabitants of this area of Wexford. The language of the area would have been difficult to understand for outsiders like James. The journey to and from Kilkenny would have taken a few days to complete. So why would James have travelled here?

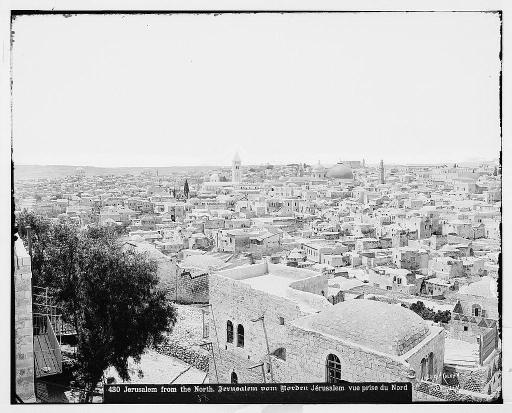

Lady’s Island 1833 taken from The Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 30, January 19, 1833

Lady’s Island is still an active pilgrimage site today. Tradition holds it has been a place of pilgrimage from the 6th century and it continues to attract pilgrims to this day. For the purpose of this post I will only focus on the evidence for pilgrimage here in the 17th century.

During the 17th century Lady’s Island was a pilgrimage site of regional importance. In the early 1607 Pope Paul V issued a plenary indulgence to all who visited here on the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lady (8th September) and on that of the Assumption (15th August).

Lady’s Island was also known as a place of healing. An account of the island written in the 1680’s states of the island

a church, builded and dedicated to the glorious and immaculate virgin Mother; by impotent and infirme pilgrims, and a Multiude of persons of all Qualities from all provinces and parts of Ireland, daily frequented, and with fervent devotion visited, who, praying and making some oblacions, or extending charitable Benevolence to Indigents there residing, have there miraculously cured of grievous Maladyes, and helped to the perfect use of naturally defective Limmes, or accidentally enfeebles or impaired Sences. (Hore 1862, 61)

Given the site’s status and its association with healing it makes sense that James would come here. Unfortunately he does not record anything of this pilgrimage other than it was completed. Given that the saints power was held to be at its strongest on the saints feast day its likely. if timing permitted, that the pilgrimage would have tried to target one of the Marian feast days.

According to Colonel Solomon Richards, writing in 1682, the ‘most meritorious’ time to visit Lady’s Island was between the 15th of August and the 8th of September (Hore 1862, 88)

Richards also describes the ritual practice of the pilgrims and we can assume that James completed his pilgrimage in one of the manners described below:

And there doe penance , going bare-leg and bare foote, dabbling in the water up to the mid leg, round the island. Some others goe one foote in the water, the other on dry land, taking care bot to wet the one nor to tread dry with the other. But some great sinners goe on their knees in the water around the island and some others that are greater sinners yet, goe three times round on their knees in the water.

Modern pilgrims walking along the edge of Lady’s Island

According to Richards the pilgrimage culminated with the making of offerings at the chapel on the Island. This was most likely the ruined medieval church.

Ruins of the medieval church on Lady’s Island

Having completed his pilgrimage James would have returned home. Ellen recovered from her illness and lived to adulthood and is recorded to have married William Mulhall. James continued to write the births and deaths of his family in his prayer-book and following his death in 1724 the tradition was continued by his youngest child William.

James and Ellens story is one that was paralleled in medieval times and even modern times, and shows how a father was prepared to do all that he could to save his child .

References

Ainsworth, J. & MacLysaght, E. 1958. ‘No 20, Survey of Documents in Private Keeping:Second Series’ Analecta Hiberbica, Vol. 1, 3-361; 363-393

Church Records pertaining to the Shee family at http://records.ancestry.com/James_Shee_records.ashx?pid=52588493

Gillespie R. 1997. Devoted People. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 90-91.

Hore, H. 1862. ‘Particulars Relative to Wexford and the Barony of Forth: By Colonel Solomon Richards, 1682.’ The Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, Ser. 2, Vol. IV, 84-92.

Lady’s Island, County Wexford, in 1833. http://www.libraryireland.com/articles/LadysIslandDPJ1-30/index.php

Lady’s Island website http://www.ourladysisland.ie/

National Library Manuscripts. Reference #32383: Power O’Shee Papers (from 1499), the property of Major P. Power O’Shee, of Gardenmorris, Kilmacthomas, (now in the National Library of Ireland), relating to the families of Shee of Sheestown, Co. Kilkenny and Cloran, Co. Tipp., and Power of Gardenmorris. XX (1958).

.

One of the oldest stones is found close to the east gable it is a simple slab with IHS design with a cross extending from the H. The left side of the stone is damaged but it is still possible to read the inscription.

One of the oldest stones is found close to the east gable it is a simple slab with IHS design with a cross extending from the H. The left side of the stone is damaged but it is still possible to read the inscription. This stone record the death of Daniel Cremin who died the 12th of Dec 1741 aged 70 along with Patrick Cremin who died Oct 7, 1776 aged 9 years. On the north side of the graveyard is an elaborate grotto which incorporates a holy well.

This stone record the death of Daniel Cremin who died the 12th of Dec 1741 aged 70 along with Patrick Cremin who died Oct 7, 1776 aged 9 years. On the north side of the graveyard is an elaborate grotto which incorporates a holy well.