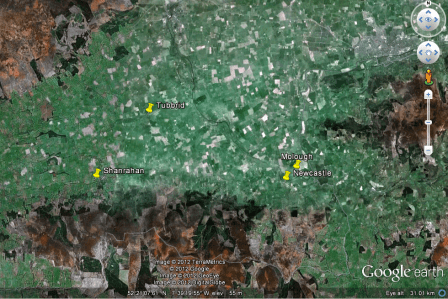

At the moment there are some really exciting community archaeology projects taking place in Ireland. I want to tell you about one project happening over the next two weeks in South Tipperary. This project involves the training of local communities to record historic gravestones at the old graveyards at Newcastle, Molough Abbey, Shanrahan and Tubbrid. The training and mentoring for the project is being provided by Historic Graves. As you can see from their website http://historicgraves.ie/ Historic Graves have successfully completed similar project all over the country.

Today I headed over to Shanrahan graveyard, located just outside of Clogheen, to see how the project works.

Shanrahan is a really interesting place, at the center of the graveyard are the ruins of a medieval parish church. The church is unusual in that it has two Sheela-na-gigs. Sheelas are figurative carvings of naked women, usually bald and emaciated, with lug ears, squatting and pulling apart their vulva. These carvings are found on medieval church, sometimes castle sites in Ireland and England.

There are lots of theories about the purpose of these carvings, some believe that were used to ward off evil, others that they were symbols of fertility, others that they were used to warn against the dangers of lust etc . If you want to find out more about these strange carvings check out the bibliography below.

John Tierney of Historic Graves, kindly brought me on a guided tour and explained how the recording is done. I also got to meet the volunteers who were all having a great time and doing an excellent job recording the inscriptions.

The project also involves the local primary schools.

The gravestones are numbered, then photographed using a special camera which provides each photo which a geo tag. This information can be used to produce a plan of the graveyard. Next the inscriptions on the stones are recorded.

Once the stones have been photographed and the inscriptions recorded , a rubbing is taken of each gravestone .

The local kids from Clogheen primary school came along for a visit and to help out with the recording.

Projects like this are really important. They help local communities become aware of the importance of Irish graveyards. Each stone has its own story and can tell alot about the social history of the time . The location of graves and style of headstone can tell us about class and religious differences . They provide a record of people who lived in the area , as well as a record of folk art for the 18th – early 19th century. They also provide imformation about the people who made the stones. Additionally projects like this make people aware of good practice in maintaining and looking after graveyards. This in turn means they are less likely to engage in bad practice like sandblasting or cleaning stones with wire brushes which ultimately damages the stones.

Just when I thought I was having a pilgrim free day John brought me to see the grave of Fr. Nicholas Sheehy 1734—1766. An opponent to the penal laws, the preist was hung , drawn and quartered after he was falsely accused of murder. The candles on the grave and the flowers immediately pointed to people coming to the grave.

John then pointed out a small hatch or door in the side of his tomb and noted he had seen a similar hatch at priests grave in Cavan also dating to the penal times.

This opening allowed people to remove soil from the grave within, the soil which was seen to be holy and have healing powers, was take away to be used for cures.

Fr. Sheehy’s tomb immediately reminded me of medieval pilgrims who were known to take dirt/earth from the saint’s grave, or cloths touch against the saint’s shrines or oil from the lamps that burned at the shrine, home with them. The tradition of healing soil is recorded in early Greek medicine, where certain soils were seen to have curative powers. In the medieval world the healing power of the earth came from the belief that the soil was a type of relic. Pilgrims believed the earth or dirt from the saints graves had been scantified because of its proximity to the saints body . There are many accounts of 19th century and even modern pilgrims taking the holy earth from the grave of the saints home with them, to use for cures and protection. At Ardmore the soil from St Declans grave was sold to pilgrims in the 19th century, while at Clonmacnoise the practice of taking earth from the grave of St Ciarán caused the walls of Temple Ciarán to become unstable and lean in. I think this could be a topic for another blog post.