Over the last few years, I’ve visited alot of holy wells all over around Ireland. St Ailbe’s holy well in the village of Emly Co Tipperary is one of the most interesting.

The village of Emly can trace its origins back to a monastery founded by the Pre-Patrican saint known as Ailbe. The saint’s death is recorded for the year 528 in the Irish annals.

Repose of Ailbe of Imlech Ibuir

The Annals of Ulster 528

His monastery known as Imleach Iubhair ‘the lakeside at a yew tree’ went on to become one of the most important ecclesiastical sites in Munster and in later centuries Emly became a Diocesan centre.

The ecclesiastical site was located at the modern Catholic church and graveyard. Unfortunately little of the early or medieval ecclesiastical remains have survived.

The annals provide some insight into what Emly would have looked like. In 1058 the great stone church (daimhliag) and the round tower (cloictheach) were burnt.

Imleach-Ibhair was totally burned, both Daimhliag and Cloictheach.

Annals of the Four Masters 1058

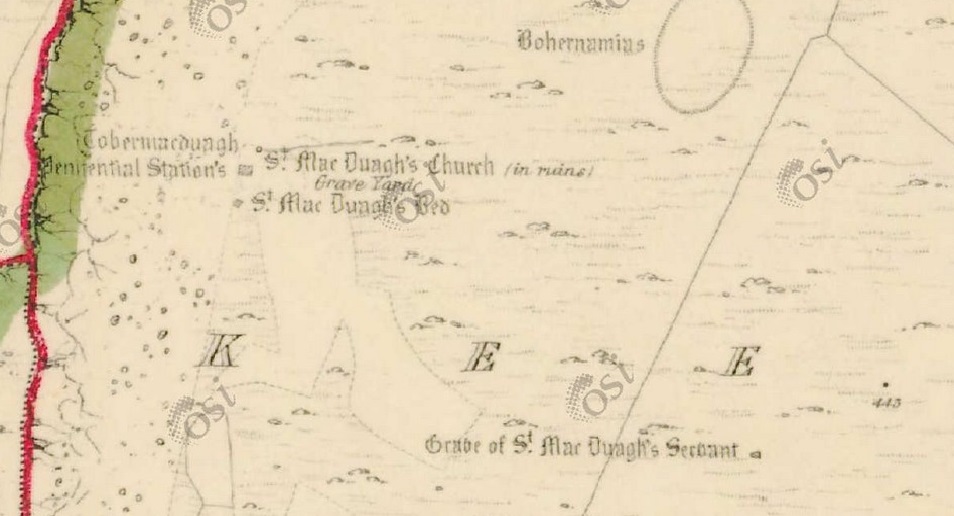

A circular enclosure surrounded the main ecclesiastical buildings. The outline of the enclosure is still preserved in the modern road and field pattern surrounding the catholic church (Farrelly 2014).

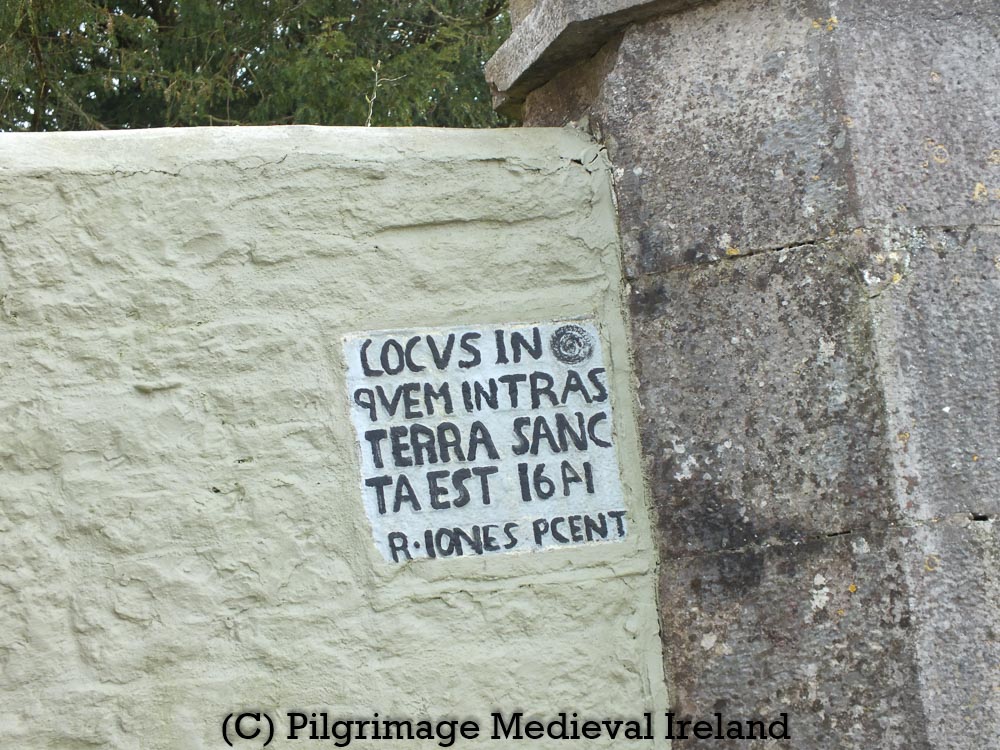

Further traces of the medieval past survive in architectural fragments incorporated into the modern graveyard wall. A stone plaque close to the main entrance to the graveyard and church which bears the inscription

LOCVS IN QVEM INTRAS TERRA SANCTA EST 1641 R. IONES PCENT

The inscription roughly translates as ‘The place wherein you enter is holy ground’ (Farrelly 2014 after pers. comm. Gerard Crotty).

A medieval stoup, ‘consisting of bowl, shaft and base, composed of a conglomeration of sandstone, granite and quartz’ sits at the east door to the modern church (Farrelly 2014).

The wall to the right of the entrance to the east end of the church incorporates two carved heads from the former medieval cathedral, along with the base of a medieval graveslab. All date to the 13th/14th-century (Farrelly 2014).

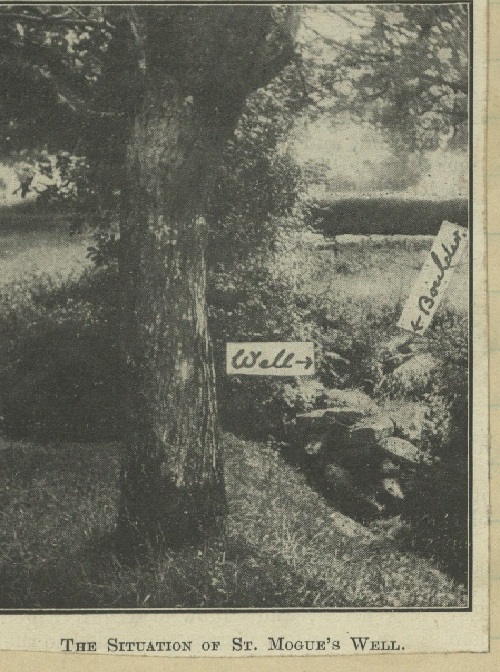

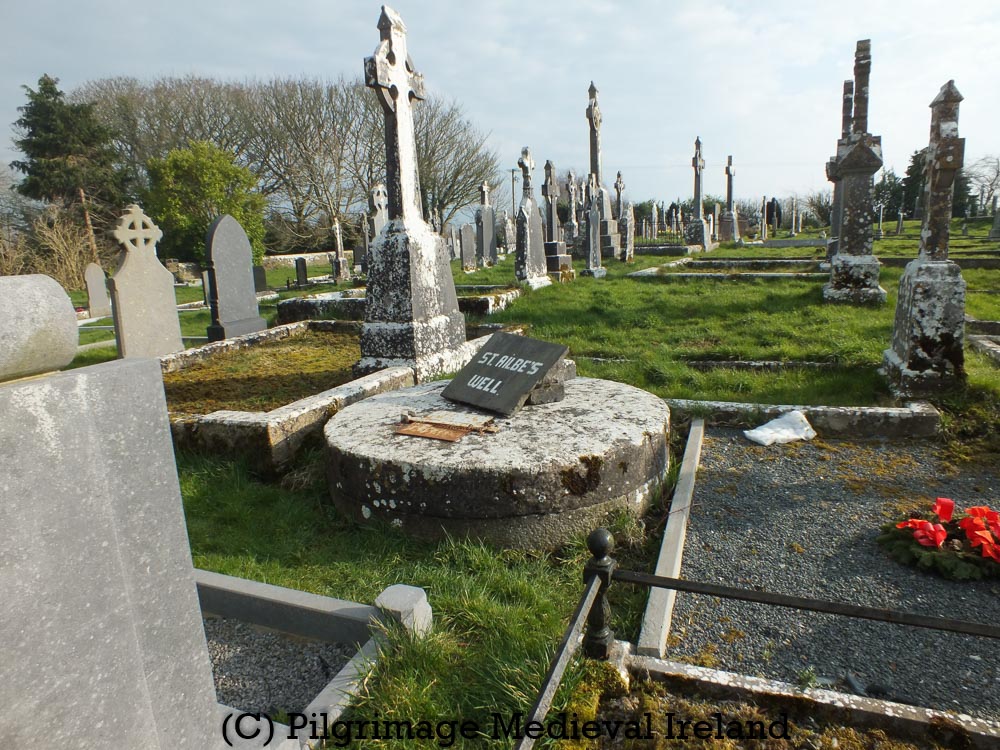

St Ailbe’s holy well can be found in the north-eastern corner of the graveyard. It was probably used as a water source for the religious community. In 1898 the well supplied the surrounding village with water.

St Ailbe’s well is a very deep spring found at the base of 5m deep circular dry-stone lined shaft (internal diameter of 1.2m). The Ordnance Survey Letter for County Tipperary written in the 1840’s suggests the well was 7m deep. The upper section of the shaft was replaced in the nineteenth century by a cut limestone surround. Accounts from the late 1890s recall that a railing surrounded the well.

During the twentieth century the top of the well was covered by low concrete capping, incorporating a metal door/hatch. Today hatch provides a view into the interior of the well.

Due to the depth of the well a torch is required to see the interior in any detail . At the base of the well you can still see the water.

According to folklore the well was formed when

St. Ailbe jumped from the top of the hill of Knockcarron to where the well stands now and that is what caused the well to be there.

Archival Reference

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0580, Page 013

The well is still visited by local people throughout the year but rounds are no longer performed.

I have not come across any medieval references to pilgrimage at the well. Rounds were performed by pilgrims up to the middle of the twentieth century. Local folk memory recalls that a pattern day was held at the well on the 12th of September, the feast of St Ailbe.

Local memory and historical sources suggest that in the past the pilgrimage rituals were focused on the holy well and an early medieval cross, known as St Ailbe’s Cross. The cross is located a short distance from the well.

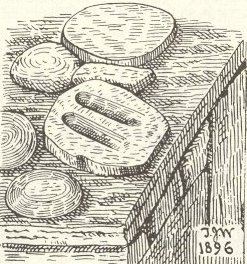

Tradition held that the cross marked the saints grave (The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0580, Page 011). The cross is made of sandstone and has an imperforate ringed cross. A small stone sits on top of the cross.

In the past pilgrims traditionally visited the holy well on the feast day of St Ailbe or within the Octave of his feast day.

In the 1930’s, pilgrims began their prayers by saying five Our Fathers and Hail Marys at the holy well. They then recited three rosaries while walking around the graveyard. If the pilgrim visited on a day other than the feast they carried out the same prayers at the holy well but recited nine rosaries while walking clockwise around the graveyard. Other accounts recall pilgrims walking around the well nine times and every three times they circle the well they say the rosary. They then made five rounds around the graveyard reciting the rosary on each round.

Pilgrims also visited St Ailbe’s cross. Its was tradition for all who passed the cross to make Sign of the Cross.

The Sign of the Cross is made by the people on it with three stones which are laid on top of it. Long ago the people used swear by the Holy Stone of Emly. Every time people respect it as they pass it by carving a cross on it with stones.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0580, Page 016

The cross was also said to cure back pain when the back was pressed against the cross and a prayer to the saint uttered. People without back pain performed the same ritual to strengthen their backs.

When a person has a pain in his back he would get it cured by putting his back against the stone and praying to St Ailbe. When a person has no pain in his back and to do the same it would strengthen his back.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0580, Page 016

The waters of the well are said to be a cure for rheumatism and also to repeal birds from damaging crops.

People take the water from the well to drink. When St Ailbe was young he was sent into a garden to keep birds off of it and since that people go to the well, and take water from it and sprinkle it on the corn to keep the birds away.

The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0580, Page 013

Although there are no records relating to pilgrimage during medieval times, Emly would surely have possessed relics of the saint and attracted pilgrims. Perhaps the tradition of devotion to the holy well and cross may be much older then the nineteenth century.

Bibliography

Farrelly, J. 2014. TS065-013 (Emly) https://maps.archaeology.ie/HistoricEnvironment/

Long, R. H. 1998. ‘Cashel and Emly Diocese. With a pedigree of Cellachan, king of Cashel, and an account of some other kings of Munster’ Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 1898, Vol. 4, No. 39, 170-185.

O’Dwyer, M. and O’Dwyer, L. 1987. The parish of Emly: its history and heritage.

O’Flanagan, Rev. M. (Compiler) 1930 Letters containing information relative to the antiquities of the county of Tipperary collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1840. Bray.

Irish Tourist Association, ‘Emly Irish Tourist Association Report,’ Tipperary Archive, accessed November 8, 2020, http://www.tippstudiesdigital.ie/items/show/1147.

Websites

Schools Collections https://www.duchas.ie